Overview of The Orion Zone

by Gary A. David

Copyright © 2000 by Gary A. David.

islandhills@cybertrails.com

A Stellar Configuration on the High Desert

To watch Orion ascend from the eastern horizon and assume its dominant winter

position at the meridian is a wondrous spectacle. Even more so, it is a startling

epiphany to see this constellation rise out of the red dust of the high desert

as a stellar configuration of Anasazi cities built from the mid-eleventh to

the end of the thirteenth century. The sky looks downward to find its image

made manifest in the earth; the earth gazes upward, reflecting upon the unification

of terrestrial and celestial.

Extending from

the giant hand of Arizona’s Black Mesa that juts down from the northeast,

three great fingers of rock beckon. They are the three Hopi Mesas, isolated

upon this desolate but starkly beautiful landscape to which the Ancient Ones

so long ago were led. Directing our attention to this “Center of the World,”

we clearly see the close correlation to Orion’s Belt. Mintaka,

a double star and the first of the trinity to peek over the eastern horizon

as the constellation rises, corresponds to Oraibi

and Hotevilla

on Third (West) Mesa. The former village is considered the oldest continuously

inhabited community on the continent, founded in the early twelfth century.

As recently as 1906, the construction of the latter village proved to be a prophetic,

albeit traumatic event in Hopi history precipitated by a split between the Progressives

and the Traditionalists. About seven miles to the east, located at the base

of Second (Middle) Mesa, Old Shungopovi

(initially known as Masipa) is reputed to be the first village established after

the Bear Clan migrated into the region circa A.D. 1100. Its celestial correlative

is Alnilam,

the middle star of the Belt. About seven miles farther east on First (East)

Mesa, the adjacent villages of Walpi,

Sichomovi,

and Hano

(Tewa) --the first of which was settled prior A.D. 1300-- correspond to the

triple star Alnitak,

rising last of the three stars of the Belt.

Nearly due north

of Oraibi at a distance of just over fifty-six miles is Betatakin

ruin in Tsegi Canyon, while about four miles beyond is Kiet Siel ruin. Located

in Navaho National Monument, both of these spectacular cliff dwellings were

built during the mid-thirteenth century. Their sidereal counterpart is the double

star Rigel,

the left foot or knee of Orion. (We are conceptualizing Orion as viewed from

the front.) Due south of Oraibi about fifty-six miles is Homol’ovi

Ruins State Park, a group of four Anasazi ruins constructed between the

mid-thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. These represent the irregularly

variable star Betelgeuse,

the right shoulder of Orion.

Almost forty-seven miles southwest of Oraibi is the primary Sinagua ruin of

Wupatki

National Monument,

surrounded by a few smaller ruins. (“Sinagua” is the archaeological term for

a group culturally similar and contemporaneous to the Anasazi.) Built in the

early twelfth century, their celestial counterpart is Bellatrix,

a slightly variable star forming the left shoulder of Orion. About fifty miles

northeast of Walpi is the mouth of Canyon

de Chelly National Monument.

In this and its side Canyon del Muerto a number of Anasazi ruins dating from

the mid-eleventh century are found. Saiph,

the triple star forming the right foot or knee of Orion, corresponds to these

ruins, primarily White House, Antelope House, and Mummy Cave. Extending

northwest from Wupatki/Bellatrix, Orion’s left arm holds a shield over numerous

smaller ruins in Grand Canyon National Park, including Tusayan near Desert View

on the south rim. Extending southward from Homol’ovi/Betelgeuse, Orion’s right

arm holds a nodule club above his head. This club stretches across the Mogollon

Rim and

down to other Sinagua ruins in the Verde Valley. As a small triangle formed

by Meissa at its apex and by Phi 1 and Phi 2 Orionis at its base, the head of

Orion correlates to the Sinagua ruins at Walnut

Canyon National Monument

and a few smaller ruins in the immediate region.

If

we conceptualize Orion not as a rectangle but as a polygon of seven sides, more

specifically an “hourglass” (connoting Chronos) appended to another

triangle whose base rests upon the constellation’s shoulders, the relative

proportions of the terrestrial Orion coincide with amazing accuracy. The apparent

distances between the stars as we see them in the constellation (as opposed

to actual light-year distances) and the distances between these major Hopi village

or Anasazi/Sinagua ruin sites are close enough to suggest that something more

than mere coincidence is at work here. For instance, four of the sides of the

heptagon (A. Betatakin to Oraibi, B. Oraibi to Wupatki, C.

Wupatki to Walnut Canyon, and F. Walpi to Canyon de Chelly) are exactly

proportional, while the remaining three sides (D. Walnut Canyon to Homol’ovi,

E. Homol’ovi to Walpi, and G. Canyon de Chelly back to Betatakin)

are slightly stretched in relation to the constellation-- from ten miles in

the case of D. and E. to twelve miles in the case of G.

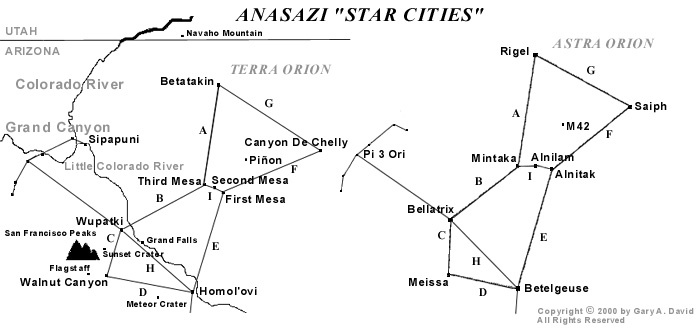

(See Diagram 1.)

|

Diagram

1

This variation

could be due either to cartographic distortions of the contemporary sky chart

in relation to the geographic map or to ancient misperceptions of the proportions

of the constellation vis-à-vis the landscape. Given the physical exigencies

for building a village, such as springs or rivers, which are not prevalent in

the desert anyway, this is a striking correlation, despite these small anomalies

in the overall pattern. As John Grigsby says in his discussion of the relationship

between the temples of Angkor in Cambodia and the constellation Draco, “If

this is a fluke then it’s an amazing one.... There is allowance for human

error in the transference of the constellation on to a map, and then the transference

of the fallible map on to a difficult terrain over hundreds of square kilometers

with no method of checking the progress of the site from the air.”1.

In this case we are dealing not with Hindu/Buddhist temples but with multiple

“star cities” sometimes separated from each other by more than fifty

miles. Furthermore, we have suggested that the “map” is actually represented

on a number of stone tablets given to the Hopi at the beginning of their migrations,

and that this geodetic configuration was influenced or even specifically determined

by a divine presence, viz., Masau’u, god of earth and death.

Referring once more to Diagram 1, we also note the angular correspondences of

Orion-on-the-earth to Orion-in-the-sky. Here again the visual reciprocity is

startling enough to make one doubt that pure coincidence is responsible. Using

Bersoft

Image Measurement

1.0 software, however, we can correlate in degrees the precise angles of this

pair of digital images seen in the diagram. (Note: The celestial image is drawn

from Skyglobe 2.04.)

|

Angle

|

Degrees

|

Difference

|

| AG Terra |

65.37

|

|

|

AG Orion

|

71.19

|

5.82

|

|

BC

Terra

|

132.60

|

|

|

BC

Orion

|

130.77

|

1.83

|

| CD Terra |

84.31

|

|

| CD Orion |

100.07

|

15.76

|

| DE Terra |

97.79

|

|

| DE Orion |

95.65

|

2.14

|

| FG Terra |

56.17

|

|

| FG Orion |

64.23

|

8.06

|

The closest correlation is between the left and right shoulders (BC and

DE respectively) of the terrestrial and celestial Orions, with only about

two degrees difference between the two pairs of angles. In addition, the left

and right legs (AG and FG respectively) are within the limits

of recognizable correspondence, with approximately six to eight degrees difference.

The only angles that vary considerably are those that represent Orion's head

(CD), with over fifteen degrees difference between terra firma and the

firmament. Given the whole polygonal configuration, however, this discrepancy

is not enough rule out a generally close correspondence between Orion Above

and Orion Below.

Solstice

Interrelationship of Villages

Another factor that precludes mere chance in this mirroring of sky and earth

is the angular positioning of the terrestrial Orion in relation to longitude.

According to their cosmology, the Hopi place importance on intercardinal (i.e.,

northwest, southwest, southeast, and northeast) rather than cardinal directions.

Of course, the Anasazi could not make use of the compass but instead relied

upon solstice sunrise and sunset points on the horizon for orientation. The

Sun Chiefs (in Hopi, tawa-mongwi) still perform their observations of

the eastern horizon at sunrise from the winter solstice on December 22 (azimuth

120 degrees) through the summer solstice on June 21 (azimuth 60 degrees), when

the sun god Tawa is making his northward journey. On the other hand, they study

the western horizon at sunset from June 21 (azimuth 300 degrees ) through December

22 (azimuth 240 degrees), when he travels south from the vicinity of the Sipapuni

(located on the Little Colorado River just over four miles upstream from its

confluence with the Colorado River)

to the San Francisco Peaks in the southwest.2.

A few days before and after each solstice Tawa seems to stop (the term solstice

literally meaning “the sun to stand still”) and rest in his winter

or summer Tawaki, or “house.” In fact, the winter Soyal ceremony

is performed in part to encourage the sun to reverse his direction and return

to Hopiland instead of continuing south and eventually disappearing altogether.

At any rate, the key solstice points on the horizon that we designate by the

azimuthal degrees of 60, 120, 240, and 300 (that is, at this specific latitude)

recur in the relative positioning of the Anasazi sky cities. For instance, if

we stand on the edge of Third Mesa near the village of Oraibi on the winter

solstice, we can watch the sun set exactly at 240 degrees on the horizon, directly

in line with the ruins of Wupatki

almost fifty miles away. The sun disappears over Humphreys Peak, the highest

mountain in Arizona where is located the major shrine of the katsinam

(also spelled kachinas, beneficent supernatural beings who act as spiritual

messengers). Incidentally, if this line between Oraibi and the San Francisco

Peaks is extended southwest, it intersects the small pueblo called King’s

Ruin in Big Chino Valley, a stop-off point on the major trade route from the

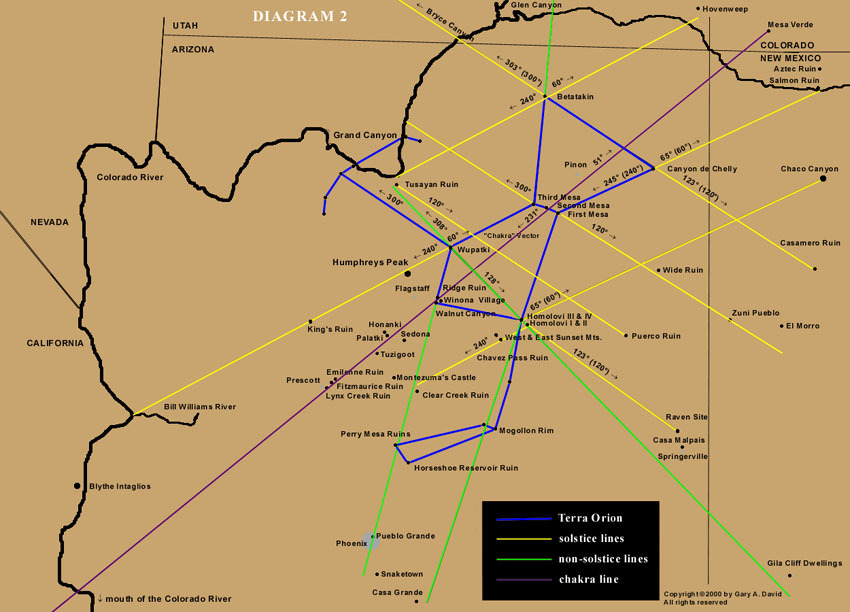

Colorado River.3. (See Diagram 2.) If

the line is extended farther southwest, it intersects the mouth of Bill Williams

River on the Colorado. Conversely, if we stand at Wupatki on the summer solstice,

we can see the sun rise directly over Oraibi on Third Mesa at 60 degrees on

the horizon. On that same day the sun would set at 300 degrees, to which the

left arm of the terrestrial Orion points. In addition, from Oraibi the summer

solstice sun sets at 300 degrees, twelve degrees north of the Sipapuni

on the Little Colorado River, the “Place of Emergence” of the Hopi

from the Third to the Fourth Worlds.

|

Diagram

2

After going

east, if we were to perch on the edge of Canyon de Chelly and not look downward

into the canyon but instead southwest at the winter solstice sunset, the sun

on the horizon would appear about five degrees south of the First Mesa Village

of Walpi. If this line were extended farther southwest beyond the horizon, it

would intersect both Sunset Crater and Humphreys Peak. Again, the reciprocal

angular relationship between the two pueblo sites remains, so from Walpi at

summer solstice sunrise the sun would appear to rise from Canyon de Chelly fifty

miles away. A northeastward extension of this 65 degree line would eventually

reach a point in New Mexico near Salmon

Ruin

and Aztec

Ruin.4.

In addition, a winter solstice sunrise line (120 degrees) drawn from Walpi past

Wide Ruin traverses the Zuni Pueblo (a tribe closely related to the Hopi) and

ends just south of El

Morro National Monument.5.

Standing during winter solstice sunrise on the edge of Tsegi Canyon where Betatakin

and Keet Seel ruins are located, we could look southeast along the edge of Black

Mesa and watch the sun come up over Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto.

In fact, the sun would be at 120 degrees on the horizon directly over Antelope

House Ruin in the latter canyon. An extension of the same line into New Mexico

would intersect Casamero Ruin.6. Later

on that first day of winter from the same spot at Tsegi Canyon we could see

the sun set at 240 degrees azimuth over the Grand Canyon more than eighty miles

to the southwest. From Tsegi a summer solstice sunrise line of 60 degrees would

intersect Hovenweep

National Monument

in southeastern Utah, well known for the archaeoastronomical precision of its

solstice and equinox markers. Again from Tsegi a sunset line of 300 degrees

would cross Bryce Canyon National Park

and Paunsaugunt Plateau, where nearly one hundred and fifty small Anasazi and

Fremont ruins have been identified.7.

If we travel one hundred and twelve miles almost due south of Tsegi Canyon to

Homol’ovi, the summer solstice sunset would appear eight degrees south

of Wupatki, which is fifty miles northwest of where we are standing. This line

(designated as H in Diagram 1) running between Homol’ovi and Wupatki

passes between Grand

Falls,

an impressive cataract along the Little Colorado River, and Roden

Crater,

a volcanic cinder cone that artist James Turrell has turned into an immense

earth sculpture, to finally end at Tusayan Ruin on the south rim of the Grand

Canyon. Again, from the reciprocal village of Wupatki the winter solstice sun

would rise just north of Homol’ovi, which is at 128 azimuthal degrees in

relation to the former site. This Wupatki-Homol’ovi line extended southeast

would pass just south of Casa

Malpais Ruin and end less than ten miles south of Gila

Cliff Dwellings.8.

From Homol’ovi a winter solstice sunrise line (120 degrees) would

pass seven degrees north of Casa Malpais 9.

and three degrees north of Raven Site Ruin

10., both north of the town of Springerville.

From Homol’ovi at winter solstice sundown (240 degrees), the sun passes

directly through East and West Sunset Mountains, the gateway to the Mogollon

rim. This line from Homol’ovi proceeds past the early fourteenth century,

thousand-room Chavez Pass Ruin on Anderson Mesa (in Hopi, Nuvakwewtaqa,

“mesa wearing a snow belt”) 11.

and continues along the Palatkwapi Trail down to the Verde Valley, ending near

Clear Creek Ruin. If we extend the summer solstice sunrise line (60 degrees)

from Homol’ovi into New Mexico, we intersect the vicinity of Chaco

Canyon,

perhaps the jewel of all the Anasazi sites in the Southwest. In this astral-terrestrial

pattern Chaco corresponds to Sirius, the brightest star in the heavens located

in Canis Major.

Thus, in this schema each village is connected to at least one other by a solstice

sunrise or sunset point on the horizon. This interrelationship provided a psychological

link between one’s own village and the people in one’s “sister”

village miles away. Moreover, it reinforced the divinely ordered coördinates

of the various sky cities come down to earth. Not only did Masau’u/Orion

speak in a geodetic language that connected the Above with the Below, but also

Tawa verified this configuration by his solar measurements along the curving

rim of the tutskwa, or sacred earth.

Non-solstice

Lines, the Grand Chakra System, and the Hopi Winter Solstice Ceremony

In addition to the solstice alignments, a number of intriguing non-solstice

lines exists to corroborate the pattern as a whole. As heretofore stated, an

extension of the solstice line between Oraibi and Wupatki (the Belt and left

shoulder of the terrestrial Orion respectively) would ultimately end on the

Colorado River at the point where a major trail east toward Anasazi territory

began. Similarly, if the non-solstice line between Walpi and Homol’ovi

(the Belt and the right shoulder respectively) were extended, it would intersect

the wrist of the constellation and terminate within five miles of the important

Hohokam

ruin site and astronomical observatory of Casa

Grande Ruins National Monument, near the Gila River one hundred and fifty

miles away. We have also already discussed the extension of the Walpi-Canyon

de Chelly solstice line (Orion’s right leg) ending up at the Salmon-Aztec

ruin area. An extension of the Oraibi-Betatakin non-solstice line (Orion’s

left leg) would bring us to Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Ruefully,

hundreds or perhaps even thousands of small Anasazi ruins were submerged by

the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam in 1963, and the few that remain can

only be reached by boat.

Another alignment of ancient pueblo sites forms the grand chakra system of Orion

and indicates the direction of the flow of spiritual energy. Drawing a line

southwest from Shungopovi/Alnilam, we pass less than five miles southeast of

Roden Crater and Grand Falls, both mentioned above. Continuing southwest the

line runs by Ridge Ruin 12., through Winona

Village 13., and into the forehead of

Orion, viz., Walnut Canyon National Monument, a significant mid-twelfth century

Sinagua ruin located in the foothills of the San Francisco Peaks. If the line

is extended farther still, it intersects the red rock country of Sedona with

its electromagnetic vortices, passing the small but gorgeously located ruin

and pictograph site of Palatki, “Red House,” as well as the larger

Honanki, “Bear House.” In the Verde Valley the newly energized vector

directly transits Tuzigoot National Monument,

a major thirteenth century Sinagua ruin of over one hundred rooms perched on

a hilltop for the probable purpose of stellar observation. The line traverses

the Black Hills of Arizona, goes by the newly excavated Emilienne Ruin 14.

in Lonesome Valley, intersects the Fitzmaurice Ruin 15.

located upon a ridge on the south bank of Lynx Creek in Prescott Valley, continues

through the small Lynx Creek Ruin at the northern base of the Bradshaw Mountains,

treks across the northern limits of the Sonoran desert, and passes near the

geoglyphs 16. in Arizona and California

to ultimately reach a point just north of the mouth of the Colorado River, perhaps

the place where the ancients migrating on reed rafts from the Third World to

the Fourth entered the territory. If we were to extend this line in the other

direction from Shungopovi, it would travel northeast across Black Mesa, passing

just southeast of Four Corners to finally end up at the major Anasazi sites

of Mesa Verde National Park in

southwestern Colorado.

In this series

of villages we have eleven both major and minor Anasazi

or Sinagua

ruins and one Hopi pueblo perfectly aligned

over a distance of over 275 miles within the framework of the tellurian Orion.

The probability that these are randomly distributed is highly unlikely and increases

the possibility that Masau’u (or some other agent perceived as being divine)

directed their positioning. This “ley line” forms a grand chakra system which

provides an inseparable link and a conduit of flowing pranic earth energy from

the Hopi Mesas to the evergreens forests of the San Francisco Peaks. More specifically,

Walnut Canyon symbolizes the Third Eye, or pineal gland (etymologically derived

from the Latin word pinus, or “pine cone”), of Orion.

At this point one might ask: Why is the template of Orion placed upon the earth

at the specific angle relative to longitude that we find it? The “chakra”

line mentioned above, which runs in part from Shungopovi/Alnilam (the Belt of

Orion) to Walnut Canyon/Meissa (the head of Orion) is 231 degrees azimuth in

relation to Shungopovi. The azimuthal direction of southwest is 225 degrees.

Thus, the axis for the terrestrial Orion is within six degrees of northeast/southwest.

If we stood at Shungopovi shortly after midnight nine centuries ago on the winter

solstice and looked southwest, we would find the middle star of Orion’s

Belt hovering directly above the southwest horizon at an altitude of

about 38 degrees. Specifically, at 1:15 a.m. on December 22, A.D. 1100, Alnilam

is at 231 degrees azimuth.17. In other

words, gazing from the central star of the earthbound belt of Orion toward its

head located in the foothills of the San Francisco Peaks where the katsinam

live, we would see the celestial constellation precisely mirror the angle of

the terrestrial configuration.

One might also question the significance of this precise time when the middle

star in Orion’s Belt is at 231 degrees. At the very moment we are watching

this sidereal spectacle, “one of the most sacred ceremonies” 18.

of the Hopi known as the Soyal is taking place in the subterranean chamber called

a kiva. Just

past its meridian Orion can be clearly seen through the hatchway. This is the

time “when Hotomkam [Orion’s Belt] begins to hang down in the sky.”

Now a powerful, barefooted figure descends the kiva ladder. He is painted with

white dots which resemble stars on his arms, legs, chest, and back. He carries

a crook on which is tied an ear of black corn, Masau’u’s corn signifying

the Above. One account identifies him as Muy’ingwa, the deity of germination

related to the aforementioned Masau’u.19.

Another calls him “Star man,” ostensibly because of his headdress

made of four white corn leaves representing a four-pointed star, perhaps Aldebaran

in the Hyades.20. At any rate, this person

takes a hoop covered with buckskin and begins to dance. His “sun shield”

fringed with red horsehair is about a foot across with a dozen or so eagle feathers

tied to its circumference. Its lower hemisphere is painted blue, its upper right

quadrant is red, and its upper left quadrant is yellow. Two horizontal black

lines for the eyes and a small downward pointing triangle for the mouth are

painted on the lower half of this striking face of Tawa. Alexander Stephen,

who witnessed the ritual at Walpi in 1891, remarked that the Star Priest stamps

upon the sipapu (the hole in the floor of the kiva that links it to the

Underworld) as a signal to start the most important portion of the ceremony.21.

This occurs just after 1:00 a.m., the time on this date in the year A.D.

1100 (the approximate onset of settlement on the Hopi Mesas) when Orion was

at 231 degrees azimuth.

As the dance rhythm crescendos, the “Star man” begins to twirl the

sun hoop very fast in clockwise rotation around the intercardinal points between

two lines of Singers, one at the north and the other at the south. With “mad

oscillations” (to quote A.M. Stephen) he is attempting to turn back the

sun from its southward journey. “All these dances, songs, and spinning

of the sun are timed by the changing positions of the three stars, Hotomkam,

overhead. Now is the time this must be done, before the sun rises and takes

up his journey.”22. If this were

merely a solar ritual, one would assume that it would take place at sunrise.

On the contrary, the sidereal position of Orion must reflect the terrestrial

positioning of the constellation, which only occurs after the former has passed

its meridian, i.e., “...when Hotomkam begins to hang down in the sky.”

Prior to dawn runners are sent out to the shrines of both Masau’u

(Orion) and Tawa (the sun) in order to deposit pahos (prayer feathers),

offerings to the two gods whose complex interaction helps to assure the seasons’

cyclic return, keeping the world in balance for yet another year.

Egyptian

Parallels to the Arizona Orion

In their bestseller The

Orion Mystery: Unlocking the Secrets of the Pyramids

23., Robert

Bauval and Adrian

Gilbert have propounded what is known as the Star

Correlation Theory. (Their book, incidentally, provided the initial impetus

for writing the present article and book-in-progress.)

These co-authors have discovered an ancient “unified ground plan”

in which the pyramids at Giza form the pattern of Orion's Belt. According to

their entire configuration described very briefly here, the Great Pyramid (Khufu)

represents Alnitak, the middle pyramid (Khafra) represents Alnilam, and the

slightly offset smaller pyramid (Menkaura) represents Mintaka. In addition,

two ruined pyramids --one at Abu Ruwash to the north and another at Zawyat Al

Aryan to the south-- correlate to Saiph and Bellatrix respectively, while three

pyramids at Abusir farther south correspond to the head of Orion. Bauval and

Gilbert also believe that the pyramids at Dashour, viz., the Red Pyramid and

the Bent Pyramid, represent the Hyades stars of Aldebaran and Epsilon Tauris

respectively. Furthermore, this schema correlates Letopolis, located due west

across the Nile from Heliopolis, with Sirius, the brightest star in the sky.

As co-author Gilbert states in a later book:

It was Bauval’s contention that the part of the Milky Way which interested the Egyptians most was the region that runs from the star Sirius along the constellation of Orion on up towards Taurus. This region of the sky seemed to correspond, in the Egyptian mind at least, to the area of the Memphite necropolis, that is to say the span of Old Kingdom burial grounds stretching along the west bank of the Nile from Dashur to Giza and down to Abu Ruwash. At the centre of this area was Giza; this, he determined, was the earthly equivalent of Rostau (Mead’s Rusta), the gateway to the Duat or underworld.24.

The region in Hopi cosmology corresponding to the Rostau is called Tuuwanasavi (literally, “center of the earth”), located at the three Hopi Mesas. Similar to the ground-sky dualism of the three primary structures at the Giza necropolis, these natural "pyramids" closely reflect the Belt stars of Orion. In addition, the portal to the nether realms is known in Hopi as the Sipapuni, located in the Grand Canyon. This culturally sacrosanct area mirrors the left hand of Orion. Whereas the Egyptian Rostau is coextensive with the axis mundi of the Belt stars formed by the triad of pyramids, the Hopi gateway to the Underworld in the Grand Canyon is adjacent to the center place but still close enough to be archetypally resonant in that regard.

In a later book entitled The Message of the Sphinx, Robert Bauval and co-author Graham Hancock describe, among many other things, the cosmic journey of the Horus-King, or the son of the Sun, to the Underworld: “He is now at the Gateway to Rostau and about to enter the Fifth Division [Hour] of the Duat -- the holy of holies of the Osirian afterworld Kingdom. Moreover, he is presented with a choice of ‘two ways’ or ‘roads’ to reach Rostau: one which is on ‘land’ and the other in ‘water’.”25. We have been blessed with a wealth of hieroglyphic texts, both on stone and on papyrus, with which we can reconstruct the Egyptian cosmology. Unless we consider petroglyphs more as a form of linguistic communication than as rock “art,” the Hopi and their ancestors, on the other hand, had no written language; hence we must rely on their recently transcribed oral tradition. In this regard the Oraibi tawa-mongwi (“sun watcher”) Don Talayesva describes an intriguing parallel to Rostau. As a young man attending the Sherman School for Indians in Riverside, California during the early years of the twentieth century, he became deathly ill and, in true shamanistic fashion, made an inner journey to the spirit world. After a long ordeal with many bizarre, hallucinatory visions, he reached the top of a high mesa and paused to look. (Is it simply another coincidence that the Hopi word tu’at, also spelled tuu’awta, meaning "hallucination" or "mystical vision," sounds so close to the Egyptian Duat-- indeed spelled by E.A. Wallis Budge, former director of antiquities at the British Museum, as Tuat, that seemingly illusory realm of the afterlife?)

“Before me were two trails passing westward through the gap of the mountains. On the right was the rough narrow path, with the cactus and the coiled snakes, and filled with miserable Two-Hearts making very slow and painful progress. On the left was the fine, smooth highway with no person in sight, since everyone had sped along so swiftly. I took it, passed many ruins and deserted houses, reached the mountain, entered a narrow valley, and crossed through the gap to the other side. Soon I came to a great canyon where my journey seemed to end; and I stood there on the rim wondering what to do. Peering deep into the canyon, I saw something shiny winding its way like a silver thread on the bottom; and I thought that it must be the Little Colorado River. On the walls across the canyon were the houses of our ancestors with smoke rising from the chimneys and people sitting out on the roofs.”26.

In this narrative

the narrow, dry road filled with cacti and rattlesnakes, where progress is measured

by just one step per year, is contrasted with the broad, easy road quickly leading

to the canyon of the Little Colorado River. A few miles east of the confluence

of this river and the Colorado River is the actual location of the Hopi “Place

of Emergence” from the past Third World to the present Fourth World. Physically,

it is a large travertine dome in the Grand Canyon to which annual pilgrimages

are made in order to gather ritualistic salt. In correlative terms the Milky

Way is conceptualized as the “watery road” of the Colorado River at the bottom

of the Grand Canyon-- that sacred source to which spirits of the dead return

in order to exist in a universe parallel to the pueblo world they once knew.

This stellar highway is alternately seen as traversing the evergreen forests

of the San Francisco Peaks, upon whose summit is a mythical kiva leading to

the Underworld. Talayesva’s account also includes traditional otherworldly motifs

such as “the Judgment Seat” on Mount Beautiful, which supports a great red stairway,

at least in his vision. (This peak is actually located about eight miles west

of Oraibi.) Furthermore, we hear of a confrontation with the Lord of Death,

in this case a threatening version of Masau’u (the Hopi equivalent of Osiris),

who chases after him. Thus, like the Egyptian journey to the Duat, the Hopi

journey to Maski (literally, “House of Death”) has two roads-- one on land and

one on water. In this context we must decide whether or not the latter is really

a code word for the sky. In the “double-speak” of the astral-terrestrial correlation

theory, are these spirits in actuality ascending to the celestial river of the

Milky Way? Is this, then, the purpose of the grand Orion schema? --to draw a

map on earth which points the way to the stars?

Returning to the subject of Orion projected upon the deserts of both Egypt and Arizona, we find both discrepancies and parallels. In terms of distinction the Egyptian plan is on a much smaller scale than the one incorporating the Arizona stellar cities, using tens of kilometers rather than hundreds of miles. Furthermore, the bright stars of Betelgeuse and Rigel are perplexingly unaccounted for in the Egyptian schema. (Recently two independent Egyptologists, Larry Dean Hunter and Michael Arbuthnot, claimed to have found all the stars of Orion represented by constructions on the Egyptian landscape. However, their terrestrial correlations are somewhat different than those originally put forth by Bauval and Gilbert. See “The Orion Pyramid Theory” in the Research/Articles section of the Team Atlantis web site.) In addition, from head to foot the Giza terrestrial Orion is oriented southeast to northwest, while the Arizona Orion is oriented southwest to northeast. Of course, the pyramids are located west of the Nile River, while the Hopi Mesas are located east of the “Nile of Arizona,”27. i.e., the Colorado River. We should also point out that Abusir is not in the correct location to match Orion’s head on the constellatory template. Bauval and Gilbert state that Abusir is “...a kilometre or so south-east of Zawyat Al Aryan.”28. (Bellatrix, or Orion’s left shoulder); it is in fact about six kilometers southeast. In other words, Abusir is nearly four miles south-southeast of where it should be according to the Star Correlation Theory. Unlike Bauval, Gilbert, and Hancock, the present author has not yet traveled to Egypt, but the consultation of any scale map will verify this statement.29.

Despite these few differences, the basic orientation of the Egyptian Orion is similar to that of the Arizona Orion, i.e., south, the reverse of the celestial Orion. According to Dr. E.C. Krupp, Director of the Griffith Observatory, this is one of the factors that invalidates the Orion Correlation Theory.30. This critique, however, is the result of a specific cultural bias in which an observer is looking down upon a map with north at the top and south at the bottom. Imagine instead that the observer is standing on top of the Great Pyramid (or for that matter, at the southern tip of First Mesa) and gazing southward just after midnight on the winter solstice. The other two pyramids (or Mesas) would be stretching off to the southwest in a pattern that reflects the Belt of Orion now achieving culmination in the southern sky. We can further imagine that if the upper portion of the terrestrial Orion were simply lifted perpendicular to the apparent plane of the earth while his feet were still planted in the same position (Abu Ruwash and an undetermined site in the case of Egypt; Canyon de Chelly and Betatakin in the case of Arizona), then this positioning would perfectly mirror Orion as we see him in the sky.

When the Anasazi gazed into the heavens, they were not looking at an extension of the physical world as we perceive it today but were instead witnessing a manifestation of the spirit world. Much like the Egyptian Duat, the Hopi Underworld encompasses the skies as well as the region beneath the surface of the earth. This fact is validated by the dichotomous existence of ancestor spirits who live in the subterranean realm but periodically return to their earthly villages in the form of storm clouds bringing the blessing of rain. Even though the eastern and western domains ruled by Tawa remain constant, the polar directions of north and south, controlled by the Elder and Younger Warrior Twins (sons of the Sun) respectively, are reversed. Thus the right hand holding the nodule club is in the east and the left hand holding the shield is in the west, similar to the star chart. However, the head is pointed roughly southward rather than northward. This inversion is completely consistent with Hopi cosmology because the terrestrial configuration is seen as a reversal of the spirit world, of which the sky is merely another dimension. An alternate explanation for the change of directions is the possibility that the pole shift which destroyed the Hopis’ Second World reversed the position of the constellation's mundane aspect.

At any rate, when looking up at Orion on a midwinter night, we can imagine that our perspectives have switched and that we are suspended high above the land, gazing to the southwest toward the sacred katsina peaks and the head of the celestial Masau’u suffused in the evergreen forests of the Milky Way. Ironically, it is here on the high desert of Arizona that we also intuit the truth of the hermetic maxim attributed to the Egyptian god Thoth (Hermes Trismegistus): “As above, so below.”

Overview of The Orion

Zone

Copyright

© 2001 by Gary A. David. All rights reserved.

Any

use of text or photographs without the author's prior consent is expressly forbidden.

Contact: e-mail islandhills@cybertrails.com

1.

Grigsby cited in Graham Hancock, Santha Faiia, Heaven’s

Mirror: Quest For the Lost Civilization (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc.,

1998), p. 127.

2. J. McKim Malville, Claudia Putnam, Prehistoric

Astronomy in the Southwest (Boulder Colorado: Johnson Books, 1993, 1989),

p. 23.

3. Inhabited from A.D. 1026 (or possibly earlier

in light of the underlying pit house) through 1300, King’s Ruin has a thirteen

room foundation, twelve of which could have been two stories high. The five

hundred pieces of unworked shells found at the site indicate substantial trade

with the Pacific. Necklaces of turquoise, black shale and argillite were also

found, one of the former material consisting of 2,031 beads that stretched sixty-six

inches long. Fifty-five graves were also discovered, containing sixty-six individuals,

most of which were buried in the extended posture with heads oriented toward

the east, awaiting Pahana’s return. Ginger Johnson, A View of Prehistory

in the Prescott Region (Prescott, Arizona: privately published,1995) pp.

8-9.

4. Occupied for a few generations after A.D. 1088,

abandoned and then reoccupied between 1225 and the late 1200s, Salmon Ruin near

the San Juan River contained from between 600 and 750 rooms. It also had a tower

kiva built on a platform twenty feet high which was made of rock imported from

thirty miles away. Ten miles north of Salmon is Aztec Ruin (an obvious misnomer)

located on the Animas River. At its peak development it contained about 500

rooms. Like the former, this latter site was originally inhabited in the early

twelfth century by people of Chaco Canyon and then re-inhabited from 1225 to

1300 by people of Mesa Verde. In addition, it has a restored Great Kiva.

5. Inhabited from A.D. 1226-1276, Wide Ruin, or

Kin Tiel, about fifty miles due south of Canyon de Chelly, is an oval shaped

pueblo of 150 to 200 rooms with a number of kivas. Atsinna pueblo, located atop

a high mesa at El Morro National Monument, was a mid-thirteenth century rectangular

structure, part of which was three stories in height. It had 500-1000 rooms

and two kivas, one circular and the other square.

--a. David Grant Noble, Ancient Ruins of the Southwest: An Archaeological

Guide (Flagstaff, Arizona: Northland

Publishing, 1989, reprint 1981).

--b. Norman T Oppelt, Guide to Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest (Boulder,

Colorado: Pruett Publishing Company, 1989, reprint 1981).

6. Constructed in the mid-eleventh century, Casamero

Ruin was a small thirty room pueblo. However, its Great Kiva, one of the largest

in the Southwest, was seventy feet in diameter-- even slightly more spacious

than the better known Casa Rinconada at Chaco Canyon about forty-five miles

to the north. Noble, Ancient Ruins, pp. 89-90; and Oppelt, Guide To

Prehistoric Ruins, p. 177.

7. Robert H. Lister and Florence C. Lister, Those

Who Came Before: Southwestern Archeology in the National Park System (Tucson,

Arizona: Southwestern Parks & Monuments Association, 1994, reprint 1993),

p. 224.

8. Located in the Mogollon Mountains of west-central

New Mexico, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument is a ruin comprised of forty

rooms in five separate caves located 150 feet above the canyon floor. The timbers

of these structures have been tree-ring dated in the 1280s. The late Mogollon,

or Mimbres, people are known for their exquisite black on white pottery, using

realistic though stylized designs. The site was abandoned by 1400. Noble, Ancient

Ruins, pp. 7-8.

9. Casa Malpais is a thirteenth century Mogollon

site of a hundred rooms with a square Great Kiva (one of the largest in the

Southwest), catacombs,

ceremonial rooms, three winding stone stairways and an astronomical observatory.

Because of the nature of the artifacts found, such as crystals, ceremonial pipes,

and soapstone fetish stands, it is thought to have been primarily a religious

center. Stan Smith, “House of the Badlands,” Arizona Highways,

August, 1993, pp. 39-44.https://members.tripod.com/Dragonrest/chambers.html

10. Located nearly ninety miles southeast of Homol’ovi

and about twelve miles north of the Casa Malpais, the Raven Site (privately

owned by the White Mountain Archeological Center) was occupied as early as A.D.

800 through A.D. 1450 and had more than eight hundred rooms and two kivas. James

R. Cunkle, Raven Site Ruin: Interpretive Guide (St. Johns, Arizona: White

Mountain Archaeological Center, no publication date).

11. Jefferson Reid and Stephanie Whittlesey,

The Archaeology of Ancient Arizona (Tucson, Arizona: The University of

Arizona Press, 1997), p. 220.

12. Occupied from A.D. 1085-1207, Ridge Ruin was

a thirty room pueblo with three kivas and a Maya-style ball court. It was also

the site of the so-called Magician’s Burial. Thought by Hopi elders to

be of the Motswimi, or Warrior society, this apparently important man was interred

with twenty-five whole pottery vessels and over six hundred other artifacts,including

shell and stone jewelry, turquoise mosaics, woven baskets, wooden wands, arrow

points, and a bead cap.

--a. Rose Houk, Sinagua: Prehistoric Cultures of the Southwest (Tucson,

Arizona: Southwest Parks & Monuments Association, 1992), p. 7.

--b. Oppelt, Guide to Prehistoric Ruins, pp. 99-100.

--c. Reid and Whittlesey, Archaeology of Ancient Arizona, pp. 219-220.

13. The eponymous Winona Village, which

was occupied at the end of the 11th century, contained about twenty pit houses

and five surface storage rooms. Oppelt, Guide To Prehistoric Ruins, p.

99.

14. The Emilienne Ruin had a foundation of twelve

rooms, most of which could have been two stories high, plus eleven outlying

one-room units.

15. The Fitzmaurice Ruin, occupied from A.D. 1140-1300,

had twenty seven rooms in which were found beads, pendants, bracelets, and eighty

one amulets, including crystals, animal fetishes, obsidian nodules (so-called

“Apache Tears”) and a curious six-faceted, truncated pyramid carved

from jadeite and measuring 1.5 centimeters wide.

--a. Franklin Barnett, Excavation of Main Pueblo At Fitzmaurice Ruin: Prescott

Culture in Yavapai County, Arizona (Flagstaff, Arizona: Museum of Northern

Arizona, 1974), p. 95.

--b. Johnson, Prehistory in the Prescott Region, p. 16.

16. Similar to the Nazca lines of Peru, these intaglios

of human, animal, and star figures, some over a hundred of feet long, were made

by removal of the darker, “desert varnished” pebbles, exposing the

lighter soil beneath. Reid and Whittlesey, Archaeology of Ancient Arizona,

pp. 127-129.

--According to the Mohave and Quechan tribes of the lower Colorado River region,

the human figures represent the deity Mastamho, the Creator of the Earth and

all life. Notice the similarity between the name of this god and that of the

Hopi earth god Masau’u. These figures are thought to be between 450 and

2000 years old.

17. Also at 1:15 a.m. on this date Bellatrix is

at 240 degrees azimuth and Meissa is at 242 degrees azimuth. Forty minutes later

Alnilam is at 240 degrees, the azimuthal degree at which the sun will set on

this same day at 5:15 p.m. Incidentally, at this winter solstice sunset time

Orion is just rising on the opposite horizon, thus emphasizing the pivotal relationship

of Orion/Masau’u and the Sun/Tawa. All astronomical computations performed

with Skyglobe. Mark

A. Haney, Skyglobe 2.04 for Windows [floppy disk] (Ann Arbor, Michigan:

KlassM Software, 1997).

18. Edmund Nequatewea cited by John D. Loftin,

Religion and Hopi Life In the Twentieth Century (Bloomington, Indiana:Indiana

University Press, 1994, reprint 1991), p. 33.

19. Frank Waters and Oswald White Bear Fredericks,

Book of the Hopi (New York: Penguins Books, 1987, reprint,

1963), pp. 158-161.

20. Richard Maitland Bradfield, An Interpretation

of Hopi Culture (Derby, England: published by author, 1995), pp. 134-135.

21. Stephen cited by Ray A. Williamson, Living

the Sky: The Cosmos of the American Indian (Norman, Oklahoma:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1989, reprint 1984), pp. 79-82.

22. Waters and Fredericks, Book of the Hopi,

pp. 161-162.

23. Robert Bauval and Adrian Gilbert, The Orion

Mystery: Unlocking the Secrets of the Pyramids (New York: Crown Publishers,

Inc., 1994), p. 125 ff.

24. Adrian Gilbert, Signs in the Sky (London:

Bantam Press, 2000), p. 65.

25. Graham Hancock and Robert Bauval, The Message

of the Sphinx: A Quest For the Hidden Legacy of Mankind (New York: Three

Rivers Press, 1996), p. 175.

--The discussion by Bauval, Gilbert, and Hancock of the Egyptian master plan

is a great deal more complex than what is merely sketched out in this article.

Their opus involves various facets such as precession of the equinoxes, star-targeted

shafts in the Great Pyramid, and other topics which are not directly relevant

to our discussion. However, this compelling work overall has challenged many

orthodox ideas in Egyptology and has spawned heated debates both on the amateur

and the professional levels.

26. Don Talayesva, Leo W. Simmons, editor, Sun

Chief: An Autobiography of a Hopi Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press,

1974, 1942) pp. 121-128.

27. Reid and Whittlesey, The Archaeology of

Ancient Arizona, p. 112.

28. Bauval and Gilbert, The Orion Mystery,

p. 139.

29. T.G.H. James, Ancient Egypt: The Land and

Its Legacy (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989, 1988), p. 41.

30. E.C. Krupp, Skywatchers, Shamans, & Kings:

Astronomy and the Archaeology of Power (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.),

pp. 290-291.

![]()