The Serpent

Knights of the Round Temple

Originally

published under the title "Secrets of the Round Towers" in Atlantis

Rising magazine, Issue 46.

(Please

be patient while graphics are loading.)

by

Gary A. David

Copyright

© 2002-2004 by Gary A. David.

Round

Towers Around the Globe

Like pyramids, circular towers

of stone are found on both sides of the Atlantic.

The common figure linking these structures, however, proves to be the

serpent or snake. Cultures as diverse as the Celts of

Ireland and the Hopi

of Arizona associate

this religiously

and psychologically charged

reptile with round temples reaching toward moisture-laden storm clouds.

Over

65 towers of exquisite masonry, many rising over 100 feet high, dot the green

countryside of Ireland. The monasteries of Monasterboice, Domhnach, and Kilkenny

were all built adjacent to earlier round towers. Some researchers claim these

commanding structures were fire temples dedicated to sun worship. Why, then,

are round towers frequently located next to healing springs or holy wells issuing

from the subterranean realm over which the snake rules? (For

some exquisite photos of Ireland’s round towers, see Martin Gray’s Places

of Peace and Power web site.)

The

round temple was a key architectural feature of the Knights

Templar, which eventually gave rise to both the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons.

In Sacred Geometry (1982), Nigel Pennick explains the symbolism of the

circular form: “Like the Pagan temples, the round churches were microcosms of

the world. In the late Middle Ages, they became the prerogative of an enigmatic

and heretical sect, the Knights Templar. The round form of church became especially

connected with the order...” Most

of Europe’s Gothic cathedrals were constructed using designs uncovered by this

fraternal organization in a 12th century excavation of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount.

Some believe that a group of Knights Templar sailed to the New England coast

in 1308 and erected a Romanesque round tower at Newport, Rhode Island.

|

|

Round

tower at Newport, RI

|

Even

earlier the Phoenicians may have spread this unique architectural feature globally

in homage to Baal, the fertility deity of rain, thunder, and lightning. In Jesus,

Last of the Pharaohs (1999), Ralph

Ellis avers that round towers were modeled after the Egyptian Benben tower

located in the Phoenix Temple at Heliopolis. (The Phoenicians were named after

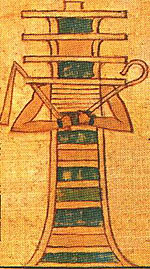

the mythical bird that rose from its ashes.) Morphologically similar to round

towers, the djed pillar was known as the “backbone of Osiris.” This column

symbolically channeled kundalini (serpent energy) up the vertebra.

|

|

Egyptian

djed pillar, anthropomorphized

|

|

|

|

Stupa with snake-like ornamentation on top |

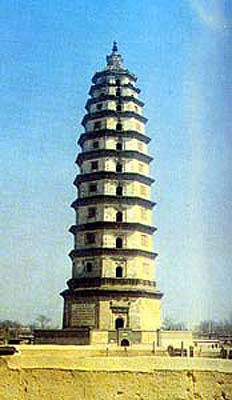

Brick

pagoda, Kaiyuan, China

|

|

|

|

Omphalos

at Delphi in Greece

|

Ouroboros

Codex Marcianus, 11th century AD |

Contrary

to the Latinate cross representing the body of Christ, a circular structure

stands for the worldly or even the satanic domain. For instance, the omphalos,

a Greek word meaning “navel,” is the oracular Stone

of Splendor at Delphi. This sacred center where tellurian serpent forces

would accumulate had the ability to directly communicate with the gods.

The figures of the serpent and the circle are united in a Gnostic and alchemical

symbol called the Ouroboros. This serpent biting its tail designates world-creating

spirit hidden within matter.

Round Towers in the Four Corners

Numerous round towers built by the Anasazi (or ancestral Hopi) can still be

found in the American Southwest. At the Chetro Ketl pueblo ruin in Chaco

Canyon,

New Mexico, a round

“tower kiva”

rises three stories high. Circular towers at Kin Kletso and Tsin Kletsin in

the same canyon are also found. The outlying villages of Salmon Ruin 40 miles

due north and Kin Ya’a Ruin 25 miles due south contain similar structures.

|

|

Tower

kiva at Chetro Ketl, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico

|

|

|

Caracol

observatory at Chichen Itzá, Yucatan, Mexico

|

The Hopi refer to round towers as “snake houses.” In a narrative describing

the origin of the Snake Clan, the wife of the culture hero Tiyo gives birth

to a brood of venomous snakes, which keeps getting loose. Masau’u

(Hopi god of death, the earth, and the Underworld-- also spelled Masau or Masaw)

explains to the snake mother why her children no longer can have a house in

which to live.

“And Masau said, ‘No, the snakes have no houses; because they have bitten and killed Hopi they should never again have a house, but should live under rocks and in holes in the ground.’ But he also said the snakes houses (the round towers) which were built for them should never again be destroyed and that all coming generations of people should know the snake’s doom, never again to have a house.” (Alexander M. Stephen, “The Journal of American Folklore,” January/March 1929)

We are obviously talking not about rattlesnake pens but either the temples or domiciles of a dangerous, snake-like race. The same Hopi myth concludes with an offering to the recovered snakes:

“When the snakes were all collected and they

were gathered together at night, they took the first snake they had found and

washed its head and gave it the name Chüa (he of the earth) and decorated it

with beads and ear rings. Then the Youth [Tiyo] opened a bag and gave the people

cotton and beads and said as the snakes had brought rain the people should now

be happy and content, and on every celebration of the Snake festival good things

would be given to them.”

Chüa

is the Hopi name of the worshipped snake that initiated their biennial rain

ceremony still performed on the Arizona high desert. This name is similar to

“Chna,” an English transliteration of the Greek word referring to the Phoenician

land of Canaan. The biblical Anakim were known to have hailed from southern

Canaan.

Andrew Collins also states that the Nephilim

were called the sons of the Anakim, and that Jewish scholars translate the word

Anak as “long-necked” or “the men with the necklaces.” The Hopi offerings of

earrings and necklaces are particularly significant because the Hopi term naaqa

means “turquoise necklace” or “ear pendant ” and anaaq means “ouch!”,

an interjection used to express the extreme pain caused by snakebite.

In addition, Baal, the Phoenician rain god mentioned above, is similar in sound

and sense to the Hopi word paal. (Because the Hopi have no “b’” sound,

“p” is the closest approximation.) This word means “liquid,” “tree sap,” “juice,”

or “broth.” Its root word pa (or paa) denotes “water,” but it

also has the sense of “wonder.”

The Hopi legend previously cited may point to the Indo-European Nagas, those

snake worshipping seafarers originating from the Indus River Valley. They are

also known as the Long Ears, who stretched their lobes with earplugs. Coincidentally,

archaeologists found an example of this artifact in an ancient pueblo ruin known

as Snaketown near modern-day Phoenix.

Templar Testament

Did the Phoenicians, who might have assisted the earliest Anasazi in building

the round towers, come to the American Southwest and establish outposts in order

to trade with the latter? Were the Knights Templar the recipients of this Naga/Phoenician

legacy, carrying forth the ancient traditions bequeathed from Egypt? Do these

structures form a global network centered around ophidian fertility symbols?

To return to our starting point, were the Irish round towers also “snake houses,”

or phallic temples used by a race of serpent people whom St. Patrick in the

5th century AD ultimately had to chase into the sea?

Perhaps we are uncovering more questions than answers. Nonetheless, round towers

survive as a testament to the awesome spiritual power of the Knights of the

Round Temple. Their serpentine eyes gaze across the centuries, now and then

sending a shiver up the spine.

![]()