The Arc of the Covenant

text, rock art photos, and maps by Gary A. David

Copyright © 2001. All rights reserved.

Graphics intensive page. Please be patient while images download.

|

|

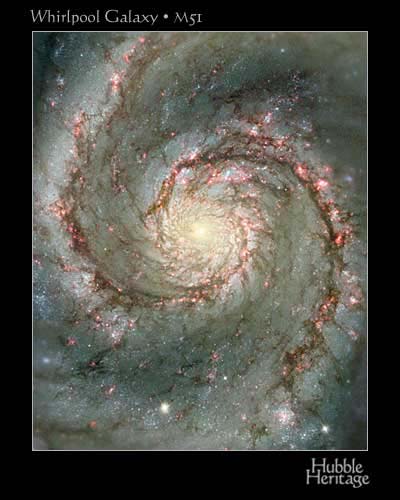

Located

from our perspective near Alkaid

(the tip of the handle of the Big Dipper) Photo courtesy of NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute |

Gazing

into the heart of a spiral galaxy, we sense a familiar path, a journey taken

long ago, resonating from another lifetime perhaps. We are awed by the vibrant

colors that the Hubble space

telescope beams back. Despite the high-tech clarity of these images, a primordial

urgency rises to greet us. If we stare long enough, the pinwheel of stars entrances

our sensibilities until we enter a golden realm of déjà vu, traveling back to

the ultimate Source. It is the Tibetan mandala, the Navaho

sand painting, and Dante's Mystic Rose all rolled into one.

Our own Milky Way drifts through space like a bioluminescent starfish. Technically

called a barred spiral galaxy, it is estimated to be over 100,000 light-years

across and 1000 light-years thick at the outer edges. The elegant theories of

modern astronomers place a mysterious black hole at the center of most galaxies,

including our own. As the ultimate manifestation of the devouring Hindu goddess

Kali (Sanskrit for "black"),

nothing escapes this juggernaut's "event horizon," or rim-- analogous

to Kali's necklace of skulls. Suns and planets, comets, galactic dust, gravity,

even light-- all are subject to its voracious attraction. To

the Maya this dark heart was known as Hunab K'u, the Only Giver of Movement

and Measure, represented by the stepped fret or spiral.1

Located upon the star road of the Milky Way in the direction between the zodiac

constellations of Sagittarius and Scorpius, our own Great Mystery beckons.

Merely one among incomprehensibly vast multitudes, the solar system where we

live is poised on the inner edge of a sidereal arc, a dozen or so of which form

our celestial spiral. This local arc is known as the Orion Arm.

The

Earth Spiral

|

|

Double-spiral

design on ceramic bowl.

Serrated edge represents clouds. Four-mile Ruin, Arizona c. A.D. 1380 Jesse Walter Fewkes, Twenty-second Annual Report Bureau of American Ethnology, 1900-1901 |

Many examples of the painted spiral exist in

ancestral puebloan pottery from the American Southwest. In

particular, the whirlpool or double-spiral motif represents the "gate

of Masau's house." 2

One of these gates is located near the Sipapuni

at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the portal through which the Hisatsinom

3 emerged from the past Third

World to the present Fourth World. The Hopi periodically journey to this

sacred area to gather ritualistic salt. Therefore, one of their names for

the Grand Canyon is Öngtupqa, literally "Salt Canyon."

Masau'u (also spelled Masau or Masaw) is the Hopi god of war,

death,

fire, the Underworld, and the earth, but he is also god of transformation.

He was present when the Hisatsinom emerged upon the surface of the earth

and began to make their migrations; he was there again when they finished

them after many centuries.

With his dibble stick and sack of seeds, Masau'u is also the humble agrarian

deity who lives in balance with the earth, providing a paradigm of purity

and simplicity. It is Masau'u with whom the Hopi established their divine

Covenant.

On

a naturalistic level the spiral represents water, an indispensable element,

especially for a desert existence. (See the photo of a

woman at Acoma pueblo balancing upon her head a ceramic jar with a spiral

design.)

The presence of a spiral petroglyph (in Hopi known as potave'yta)

can mean that a water source is or was nearby. One of the major Hopi shrines

is called Potavetaka (literally, "spiral nest"), or Point Sublime

on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. Here again we see the spiral motif

--an icon of passage or transcendence-- associated with the canyon that

the Hopi consider their Place of Emergence. In addition to water, the spiral

can refer to the whirlwind or "dust devil," a sometimes malevolently

destructive force in nature. On the other hand, whirlwinds frequently precede

rain, so they can be viewed as propitious.

|

|

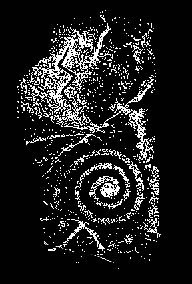

Stylized

spiral petroglyph with "pueblo" symbol at the center.

Near Homol'ovi Ruins State Park, Arizona. |

In rock art the spiral

connotes migration across the surface of the earth, especially if it is

adjacent to footprints carved in the stone. In this context a spiral signifies

the number of rounds, or pasos 4,

a clan made as it journeyed though the centuries toward its ultimate goal

of the sacred Center of the World, what the Hopi call Tuuwanasavi,

namely the three Hopi Mesas. While a Muslim's circumambulation of the Kaba

in the holy city of Mecca may take a dozen hours, the Hisatsinom/Hopi circumambulatory

migration around their axis mundi took a dozen generations, but probably

many more. During this time the Ancient Ones built pueblo villages, lived

there for a number of generations, then moved on when Masau'u instructed

them to do so.

|

|

Petroglyph

of lightning above spiral at Tsankawi Mesa, New Mexico.

Drawing by Dawn Senior |

In

general, the spiral found in both rock art and ceramics may simply connote

motion, with a clockwise spiral denoting ascension and a counterclockwise

spiral denoting descension. 5

(Was it not Jung who stated that clockwise motion represents the conscious,

while anticlockwise motion signals the unconscious?) According to author

Ani Bealaura, the spiral is manifested in the upper and middle worlds in

a direction opposite to that of the underworld. "The right hand, deocil,

or clockwise motion in Celtic belief represents the emerging, growing, material

manifestation of energy. This is the direction in which one would cast the

circle of protection and send energy into the environment. It is also used

to banish unwanted energies. The left hand, widdershin, or counter clockwise

motion represents the inward turn and to draw energy into material manifestation.

It is the principle of grounding energy. It is also used to take the inner

journey of gaining insight and enlightenment, and takes one to the 'underworld'

or 'dreamtime'. It is also related to seeking Cerridwen's Cauldron of Inspiration."

6 The mythological poet Robert

Graves claims that the Celtic god Bran (the Greek Cronos and the Roman

Saturn, whom we have identified with the Hopi Masau'u) was associated with

the alder, whose buds are set in a spiral pattern. This, he says, is "a

token of resurrection. 7. Graves

also recalls the Celtic designation for the megalithic site of Newgrange

in Ireland as the Spiral Castle. "In front of the doorway of

New Grange there is a broad slab carved with spirals, which forms part of

the stone henge. The spirals are double ones: follow the lines with your

finger from outside to inside and when you reach the centre, there is the

head of another spiral coiled in the reverse direction to take you out of

the maze again. So the pattern typifies death and rebirth..." 8

John Frayne, an artisan of Celtic jewelry, states that

spiral of opposing directions refer to solstice suns: "A loosely wound,

anti-clockwise spiral represented the large summer sun. A tightly wound,

clockwise spiral represented their shrinking winter sun."

9

|

|

Noon

on summer solstice, triangle of light enters spiral.

Homol'ovi, Arizona |

|

|

Spiral

petroglyph at the V-Bar-V Ranch, Verde Valley, Arizona.

This tight spiral is reminiscent of the coiled plaques that the Hopi weave from yucca fibers. (View photo of old Hopi kachina coil basket.) |

"This

is a coil basket symbolizing the road of life. It is called "Boo-da", meaning

some great test which we will experience during our journey. Hopi tradition

says we started our travel from the center or beginning of life, when life

was perfect. But soon we began to face new obstacles. Small groups of ambitious

minded men wanted to change their ways away from the original path. There

were only small groups at first, but with time they increased to great numbers.

Those who wanted to keep to their original ways became fewer and fewer. Since

mankind has lost peace with one another through the conflict because of the

new ways, the Great Spirit, the Great Creator has punished the people in many

ways. Through all of this there was always a small group who survived to keep

the original ways of life alive. This small group are those who adhere to

the laws of the Creator, who keep the spiritual path open, out from the circle

of evil. According to our knowledge, we are not quite out of the circle. The

men with ambitious minds will decrease, while the people of good hearts, who

live in harmony with the earth, we will increase until the earth is rid of

evil. If the Hopi are right, this will be accomplished and the earth will

bloom again. The spiritual door is open, why not join the righteous people?"

11

"This

is a coil basket symbolizing the road of life. It is called "Boo-da", meaning

some great test which we will experience during our journey. Hopi tradition

says we started our travel from the center or beginning of life, when life

was perfect. But soon we began to face new obstacles. Small groups of ambitious

minded men wanted to change their ways away from the original path. There

were only small groups at first, but with time they increased to great numbers.

Those who wanted to keep to their original ways became fewer and fewer. Since

mankind has lost peace with one another through the conflict because of the

new ways, the Great Spirit, the Great Creator has punished the people in many

ways. Through all of this there was always a small group who survived to keep

the original ways of life alive. This small group are those who adhere to

the laws of the Creator, who keep the spiritual path open, out from the circle

of evil. According to our knowledge, we are not quite out of the circle. The

men with ambitious minds will decrease, while the people of good hearts, who

live in harmony with the earth, we will increase until the earth is rid of

evil. If the Hopi are right, this will be accomplished and the earth will

bloom again. The spiritual door is open, why not join the righteous people?"

11

Is it merely a coincidence that this Hopi term is a homonym for Buddha,

the primary figure in one of the world's great religions? We are reminded

of the Dhammapada, the spiritual path taken by followers of the Enlightened

One, and of the Noble Eightfold Path: 1. right understanding 2. right purpose

3. right speech 4. right conduct 5. right vocation. 6. right effort 7. right

alertness 8. right concentration. Those who follow these precepts may in

Hopi terms be the ones "...who adhere to the laws of the Creator, who

keep the spiritual path open..." In addition, the "circle of evil"

is reminiscent of the transmigratory Wheel of Life.

On

a more psychospiritual level the spiral represents a gateway between worlds

or dimensions. It is the doorway through which the shaman begins his or

her ecstatic quest from the physical to the spiritual plane. (Note: The

word spiral comes from the Latin spira, "coil," while the

term spirit is derived from the Latin spirare, "to breathe.")

In a ritualistic trance the shaman's "breath-body" searches the

interstices of the spirit world for a specific cure or a personal vision

to bring back to the tribe. Thus, the spiral functions as a portal or gateway

from the mundane to the eternal realms. The Yaqui sorcerer don Juan Matus

calls these respective states the tonal and the nagual, although

it is much more complex than this simple dichotomy. 12

Anyone well versed in the techniques of non-ordinary reality, however,

can gain access to the latter, as we have seen in the tutelage of Carlos

Castaneda.

The morphology of the spiral is also manifested in the "vortex"

areas located in many spots around the globe-- for instance, those in the

Sedona, Arizona region. In Terravision: A Traveler's Guide to the Living

Planet Earth, Page

Bryant defines the term: "A vortex is a mass of energy that

moves in a rotary or whirling motion, causing a depression or vacuum at

the center.... These powerful eddies of pure Earth power manifest as spiral-like

coagulations of energy that are either electric, magnetic, or electromagnetic

qualities of life force." 13

The vortices can be likened to various acupuncture points upon the etheric

body of the Earth. An electric (yang) vortex --Bell Rock and Airport Mesa,

for instance-- energizes and enlivens the body and the mind, creating or

rejuvenating a sense of optimism or faith. On the other hand, a magnetic

(yin) vortex --such as Red Rock Crossing-- calms and heals the psyche. It

also encourages the flow of creative or artistic energy and may even stimulate

the brain's temporal lobe to variably induce vivid memories, visions, lucid

dreams, and past life or out-of-body experiences. An electromagnetic vortex

--Boynton Canyon, for example-- readjusts any physical, mental, emotional,

or spiritual imbalances one may be experiencing. The native peoples have

used these earth spirals for millennia, and they remain a natural source

of invigoration and regeneration today.

A similar theory posits a matrix of "dome centers" enclosing sacred

sites all across the Earth. These canopies of etheric energy are thought

to exist spatially between spirit and matter. Co-authors Richard

Leviton and Robert Coons claim that the domes as they are experienced

today are merely memories encoded in Gaia's etheric body of the quasi-material

domes that have appeared three times before in our planet's history (reminiscent

of, though not directly corresponding to, the series of Hopi "Worlds"):

"It is... not accurate to construe the Domes as mechanical material

vehicles according to our customary understanding; they are more like transdimensional

magnetic/energy facilitators overlaid on the physical landscape. In the

first Dome Presence there were no humans on Earth; in the second Dome Presence

there was primitive human life; and during the third Dome Presence there

were some humans who could clearly see the Domes and understand their function.

What these early humans saw is recounted in various ancient mythologies

(notably the Irish and Sumerian) as the Houses of the Sky Gods."

14 These resonance patterns acted as both terrestrial havens

for the gods from above and instructional centers for spiritual novitiates.

"Dome enclosures were like immaculate, high consciousness meditation

halls where human awareness could be healed, uplifted, even interdimensionally

transported through the domed exit points in the Houses of the Gods, facilitated

by megalithic engineering." 15

Elsewhere in this article the co-authors identify these energy forms as

"wise domes" (as in wisdom-- the missing "e"s

belonging to the Elohim, the Sons of Light) which assisted the "magelithic"

(as in magus) cultures. 16

The domes are connected by a nexus of "dome lines," or "pulsating

energy channels," which are similar to ley lines. Radiating centrifugally

from these sacred energy loci are spiral arms generated in harmony with

the Golden Proportion.

The Golden Mean Spiral

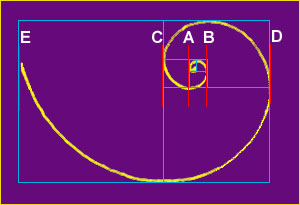

This

special type of spiral is created in nature according to what is called

the Golden Mean, Golden Section, or Divine Proportion, which is simply the

ratio (phi) of 1 : 1.6180339... It is derived from Fibonacci's

series, or a numerical list whereby each new number is the sum of the previous

two numbers: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144... ad infinitum.

Regardless of how large the spiral becomes, the ratio of its dimensions

remains constant. For instance, the proportion AB to AC is the same as BC

to BD or CD to CE.

This

special type of spiral is created in nature according to what is called

the Golden Mean, Golden Section, or Divine Proportion, which is simply the

ratio (phi) of 1 : 1.6180339... It is derived from Fibonacci's

series, or a numerical list whereby each new number is the sum of the previous

two numbers: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144... ad infinitum.

Regardless of how large the spiral becomes, the ratio of its dimensions

remains constant. For instance, the proportion AB to AC is the same as BC

to BD or CD to CE.

The Golden Mean can also be applied geometrically to form the Golden Rectangle,

the sides of which contain the phi ratio. The dimensions of the fabled Ark

(spelled with a "k") of the Covenant is known to have conformed

to Golden Mean proportions. This Hebrew artifact was 45 inches in length

and 27 inches in both width and height. (2.5 cubits by 1.5 cubits by 1.5

cubits, with an ancient cubit equaling 18 inches.) 17

Although the sacred object was considered sacrosanct, it has apparently

disappeared, and speculation on its whereabouts continues.

The growth of many objects in nature is determined by the Golden Mean, including

the whorl pattern of sunflowers, pine cones, the distribution of leaves

on a stem, fingerprints, and hurricanes. Undoubtedly the Christian mystical

poet and painter William

Blake intuited the essence of the Golden Mean in one of his little "Songs

of Experience":

"Ah

Sun-flower! weary of time,

Who

countest the steps of the Sun:

Seeking

after that sweet golden clime

Where

the travellers journey is done.

"Where

the Youth pined away with desire,

And

the pale Virgin shrouded in snow:

Arise

from their graves and aspire,

Where

my Sun-flower wishes to go." 18

Besides the obvious golden/sunflower reference, the pun on "aspire,"

viz., "a spire," points to a synonym for the word spiral. And

perhaps we would not be overly stretching the matter to note the pun on

the word "pined" in reference to the evergreen, whose cones develop

their seeds according to Fibonacci's ratio. In other natural forms such

as the chambered nautilus and the horns of the bighorn sheep, growth occurs

by addition to the open end of the spiral. The object always retains its

geometric shape according to the phi ratio; thus, the morphology remains

proportional.

|

|

|

Horn

size is a symbol of rank, with male horns sometimes weighing as much

as 30 lb.

|

Petroglyph

of bighorn sheep (left)

and possibly two elks. Perry Mesa, Arizona |

|

|

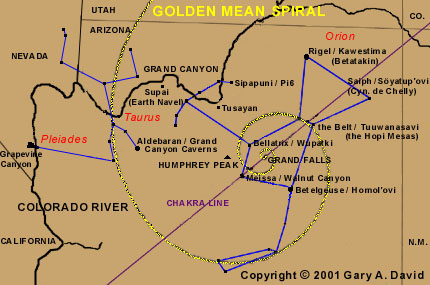

Diagram

1

This Golden Mean spiral starts at the Heart chakra located at Grand Falls, arcs through the San Francisco Peaks (home of the kachinas, or katsinam), sweeps by Oraibi, Shungopovi, and Walpi (the Belt), intersects Orion's right hand, circles into the Hyades horns, and passes through Gamma Tauri. |

|

|

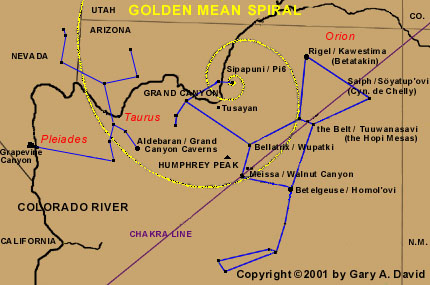

Diagram

2

This Golden Mean spiral starts at the Sipapuni (Hopi "Place of Emergence"), arcs through Oraibi (oldest continuously inhabited community on the continent, settled c. A.D. 1100), swings through the Third Eye chakra of Orion at Walnut Canyon, then continues its sweep through the middle of the horns of Taurus. |

|

|

Double

spiral, clockwise (left) and counterclockwise (right), with staff.

Homol'ovi Ruins State Park, Arizona |

The archetypal motif of the entwined twin snakes is found at differing times

in diverse parts of the world. Many Westerners are now familiar with the

age-old Tibetan practice of kundalini, a form of Tantric yoga. The word

Kundala means "coiled," and refers to the energy of the

cosmic serpent asleep at the base of the spine. In addition to the chakras,

or energy wheels, positioned along the spinal column (Susumna), two

subtle nerves called the Pingala and the Ida form a double

spiral that interlaces the backbone, channeling solar (masculine) and lunar

(feminine) energy respectively up and down the spine. The chakra system

apparently is not restricted to Asia. Sir John Woodroffe (a.k.a. Arthur

Avalon) remarks in this regard: "I am told that correspondences are

discoverable between the Indian (Asiatic) Sastra and the American-Indian

Maya Scripture of the Zunis [sic] called the Popul Vuh. My informant tells

me that their 'air-tube' is the Susumna; their 'twofold air-tube' the Nadis

Ida and Pingala. 'Hurakan,' or lightning, is Kundalini, and the centres

are depicted by animal glyphs." 23

An epithet for Huracan (or Hurricane), the lightning deity

of the Maya, is "Heart of the Sky," 24

the exact phrase used to describe the correlative Hopi god Sotuknang. The

Hopi glyph and accompanying hand gesture for lightning is formed by a "...sinuous,

undulating motion..." i.e., a spiral. Another Hopi design for lightning

is a series of lozenges, while yet another is shaped like a modern expandable

coat rack-- both of which are two-dimensional representations of the 3-D

double spiral. 25 Significantly,

Frank Waters and White Bear Fredericks discuss in detail the Hopi version

of the chakra system, which has many parallels to the Asian one. 26

To exemplify the spiral icon, the renown mythologist Joseph Campbell draws

our attention to a Sumerian libation cup of King

Gudea (c. 2000 B.C.), which features a pair of copulating vipers interlaced

along a staff. 27 He

also discusses the tenth century Cross

of Muiredach located in Monasterboice, Ireland. This elaborately carved

stone cross depicts spiral serpents interlacing three human heads, while

on its upper portion "the Right Hand of God" touches a halo-like

disk. 28 In addition, Campbell

cites the fifteenth century Aztec codex Fejérváry-Mayer,

which depicts a pair of serpents (possibly rattlesnakes) intertwined upon

an altar with their heads facing outward in opposite directions. 29

Finally, he mentions the Navaho medicine man Jeff King, who was

born in New Mexico in the mid-nineteenth century and died at about age 110.

From boyhood this traditional Navaho frequently visited a stone carving

near a cave of a particular mountain near his home. This carving represented

two entwined spiral snakes positioned with their heads pointing east and

west. Unfortunately the sculpture was lost when a rock overhang collapsed

and it was washed away. 30

These exemplars from widely disparate cultures demonstrate the universal

nature of the spiral, in both its therapeutic and its shamanistic dimensions.

Originating from the healing snakes of Asclepius, the ophidian emblem, of

course, is widely recognized today in reference to the medical profession.

In

all the excitement about the human genome mapping project and its potential

for medical science, we sometimes forget the ineffable beauty of the DNA

double helix, that spiral staircase gently uncoiling itself with a mathematical

precision inside every living thing.

In

all the excitement about the human genome mapping project and its potential

for medical science, we sometimes forget the ineffable beauty of the DNA

double helix, that spiral staircase gently uncoiling itself with a mathematical

precision inside every living thing. Perhaps the ancients intuited even more so than we do its spiritual significance

beyond aesthetics. For instance, from the Introduction to his intriguing

online book entitled Living

In Truth: Archaeology and the Patriarchs, Charles N. Pope writes:

"The double helix or twisted pair was actually used as the fundamental

literary structure of the Torah. Torah is customarily translated as 'Teachings'

or 'Law.' However, the ruling class of ancient royal society was conversant

in many languages. According to the early 1st Century AD Jewish master Philo

of Alexandria, Moses studied the languages of all 70 nations of the known

world. The related roots 'tor,' 'tort,' 'tur,' 'ter,' etc. are found in

many other tongues, including Greek and Latin. They are the basis of common

English words such as tornado, torture, torment, torsion, turbine, storm,

turban, tour, tower, turret and turn, all of which denote or imply 'twisting.'"

In this regard we are startled by the fact that a New World native people

like the Hopi would use a similar etymology. Specifically, the Hopi word

tori means "twisted spirally" while the word toriritaqa means

"whirlwind." The village at the base of Second Mesa is called Toreva, or

Toriva, literally "twist water," probably referring to a spring.

Perhaps the ancients intuited even more so than we do its spiritual significance

beyond aesthetics. For instance, from the Introduction to his intriguing

online book entitled Living

In Truth: Archaeology and the Patriarchs, Charles N. Pope writes:

"The double helix or twisted pair was actually used as the fundamental

literary structure of the Torah. Torah is customarily translated as 'Teachings'

or 'Law.' However, the ruling class of ancient royal society was conversant

in many languages. According to the early 1st Century AD Jewish master Philo

of Alexandria, Moses studied the languages of all 70 nations of the known

world. The related roots 'tor,' 'tort,' 'tur,' 'ter,' etc. are found in

many other tongues, including Greek and Latin. They are the basis of common

English words such as tornado, torture, torment, torsion, turbine, storm,

turban, tour, tower, turret and turn, all of which denote or imply 'twisting.'"

In this regard we are startled by the fact that a New World native people

like the Hopi would use a similar etymology. Specifically, the Hopi word

tori means "twisted spirally" while the word toriritaqa means

"whirlwind." The village at the base of Second Mesa is called Toreva, or

Toriva, literally "twist water," probably referring to a spring.

Is it merely a coincidence that the syllable denoting spiral is the

same in many different languages all across the world, including the Uto-Aztecan

language of the Hopi? Is it not more likely that some degree of intercultural

exchange in very ancient times should cause the root word tor to

be found on a global basis? We should remember that this is not just some

widely dispersed common image which could be explained by the theory of

universal archetypes, but instead a mutually occurring phoneme. Both the

spiral form and its specific signifier were apparently necessary for its

dissemination.

According to J.E. Cirlot's A Dictionary of Symbols, "The double

spiral represents the completion of the sigmoid line, and the ability of

the sigmoid line to express the intercommunication between two opposing

principles is clearly shown in the Chinese Yang-Yin symbol."

31 Obviously the iconography

of the spiral is sacred beyond belief, superseding any belief systems to

reach deeply into the processes of both history and biology.

The Healing Spiral

We have talked about the spiral in nature, but what about the nature of

the spiral? In essence, the three-dimensional spiral assumes its form by

merging the circle (eternal) and the line (temporal). We may think of particular

cultures (Hindu and Buddhist, for instance) tending toward the former, with

their weary cycles of ceaseless incarnation, suffering, and death-- all

of it illusory, all of it maya. (i.e., The eye is on fire; forms

are on fire. The ear is on fire; sounds are on fire. The nose is on fire;

odors are on fire, etc. "And with what are these on fire?" "With

the fire of passion, say I, with the fire of hatred, with the fire of infatuation;

with birth, old age, death, sorrow, lamentation, misery, grief, and despair

are they on fire." 32)

On the other hand, Western culture (heavily influenced by Judaism, Zoroastrianism,

and Christianity) is decidedly linear, with a clear beginning and an eventual

yet inevitable end of time (i.e., "I am Alpha and Omega..." 33).

This continuum is punctuated by either revelations or theophanies, which

are appearances of the divine within the temporal, most notably the incarnation

of Christ at the very center of the historical time span.

In his short but masterful book The Tragic, Sacred Ground, Erling

Duus underscores the paramount importance of the spiral as a mythological

paradigm for our time: "The spiral is crucial, for in it the captivity

of the sheer circle is broken, penetrated by the linear movement of historical

time, while time is relieved of its burden and its homelessness. Where and

when the two meet 'there is a whirlpool effect' and then a transformation

wherein the spiral is created, maintaining yet liberating the circle and

the line." 34 In

other words, the line gives to the circle's sometimes stupefying languor

a sense of ultimate direction, optimism, and eschatological expectation.

Conversely, the circle gives to the line's frequently rootless monomania

a sacred haven in the womb-arc of the natural world. When the spatial virtues

of the circle and the temporal virtues of the line are fused, the result

is the regenerative space-time of the spiral. Duus places his discussion

within the context of the Lakota (Sioux). This tribe's central territory

was the Black Hills of South Dakota,

which were invaded by white settlers seeking gold in violation of the 1868

Fort Laramie Treaty. (Although his book speaks primarily about the Northern

Plains, it echoes the general experiences of most Native American tribes,

including those of the Hopi and the Diné of

the American Southwest.) The Lakota, whose ethos is embodied in the icon

of the medicine

wheel, were confronted by the Whites, whose doctrine of Manifest Destiny

justified the "straight and narrow" march of progress, at least

in their own minds. As we know all too well from the history books, the

clash of these two sets of values ostensibly played itself out with tragic

consequences. This interpretation, however, is absolute only to the extent

that we view the conflict purely in either/or terms: either

the circle or the line.

If we instead embrace the spiral, a dialectic is created whereby we transcend

the limitations of both thesis and antithesis, matriarchy and patriarchy,

conservative and progressive, etc., while achieving in the process a genuine

liberation beyond dualism. In no way is this an attempt to sidestep or deny

the genocidal atrocities perpetrated by deracinated Europeans upon the native

peoples of the Americas. The fact remains, however, that Europeans journeyed

to the "New World" with their linear paradigm, perhaps with the

ultimate albeit unconscious goal of experiencing the cyclic paradigm of

Native Americans, and vice versa. In a sense each culture needed to perceive

the other as an Other, thereby creating the icon of the spiral, which

speaks both from the heart and to the heart in purely visionary terms. Reflecting

vastly different world views, the symbols of circle and line were perhaps

destined to be subsumed by this greater icon, viz., the healing spiral which

rises above, conquering all polarities in its arc of reconciliation.

Not only does the spiral include history in its spiritual sweep, but it

also encompasses biology, even allowing for the theory of evolution. Just

as a cart, one with innumerable wheels perhaps, slowly moves forward in

a straight line, so the process of evolution is simultaneously cyclic and

linear. Again, Cirlot's dictionary states that the spiral is in fact "A

schematic image of the evolution of the universe." 35

It is no coincidence, then, that the term evolution (e-

"out" + volvere "to roll") means "to unroll"

or "to open outward"-- the precise motion of the spiral.

The paleontologist and Jesuit priest Teilhard

de Chardin remarks on the shift from the 2-D to the 3-D spiral in evolutionary

terms: "We have no longer the crawling 'sine' curve, but the spiral

which springs upward as it turns. From one zoological layer to another,

something is carried over: it grows, jerkily, but ceaselessly and in

a constant direction. And this 'something' is what is most physically

essential in the planet we live on."36

Teilhard may well have said "...physically and spiritually essential,"

for he believes that all of Creation is an evolutionary process leading

to what he terms the Omega Point. Forming the spiral axis of universal love

at the heart of all centers, even God Himself is not exempt from the process

and does not stand apart. He instead evolves along with the rest of Gaia

and Her species toward the locus of convergence, viz., the culmination of

cosmogenesis. In the increasing complexification of life, there is unification

of spirit without the loss of either personal identity or humanity. Teilhard

does not perceive evolution in the same light as do most scientists, however,

whose paradigm conceives of the process as an ever widening spiral, devoid

of purpose or goal. Teilhard conversely sees it as cosmic involution,

irreversibly arcing upward and inward. It is a galactic path whereon evolutionary

travelers are both pulled forward and animated by the supreme focus of the

transcendent Omega. In these terms the spiral not only heals,

it also redeems.

The Sky Spiral

Here we return to the celestial, though --following the true nature of our

subject-- on a different level. If we conceptualize the spiral as uniting

the eternal and the temporal (again, circle and line), we may also see this

figure linking sky and earth. Historian of religions Mircea

Eliade provides evidence of this from an initiation ceremony performed

by the Wiradjuri tribe of Australia.

"... the men cut a spiral piece of bark which symbolizes the path between

sky and earth. In my opinion this represents the reactivation of the

connections between the human world and the divine world of the sky. According

to the myths the first man, created by Baiame [highest of the Gods],

ascended to the sky by a path and conversed with his Creator. The role of the

bark spiral in the initiation festival is thus clear--as symbol of ascension

it reinforces the connection of the sky world of Baiame." 37

"Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity." 43

As

we have seen, the Spiral, or "gyre," is the elemental

gate between worlds, realms, dimensions, individual life

spans. Perhaps our current onus should be to help stabilize the

dipole of the revolving/evolving axis which the Hopi warrior twins

are keeping in precarious balance. Maybe the center can hold,

if only we abide by the Arc of the Covenant and heed the hermetic

maxim "As Above, so Below." If we manage to do this, the

Creator just might let us walk a while longer upon the Spiral's

numinous path.

|

Copyright

© 2001 by Gary A. David. All rights reserved.

Any

use of text, photographs, or diagram maps without the author's prior

consent is expressly forbidden.

E-mail address:

islandhills@cybertrails.com

HOME

Footnotes

1. Hunbatz Men, Secrets of Mayan Science/Religion, Diana

Gubiseh Ayala & James Jennings Dunlap II, translators (Santa

Fe, New Mexico: Bear & Company, 1990), pp. 34-35.

2. Alex Patterson, Hopi Pottery Symbols (Boulder: Johnson

Books, 1994), p. 29.

3. Hisatsinom refers to the ancestral Hopi. They are frequently

misnamed the Anasazi, which is a Diné (Navaho) word meaning "Ancient

One" or "Ancient Enemy."

4. Frank Waters and Oswald White Bear Fredericks, Book of the

Hopi (New York: Penguin Books, 1987, reprint 1963), p. 35.

5. James R. Cunkle, Talking Pots: Deciphering the Symbols of

a Prehistoric People (Phoenix, Arizona: Golden West Publishers,

1996, 1993), p. 26.

6. Ani Bealaura, "The Celtic Circles of Existence," A

Book of Shadow and Light, unpublished manuscript.

7. Robert Graves, The White Goddess: A historical grammar of

poetic myth (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976, 1948),

pp. 171-172.

8. Ibid., p. 103.

9. John Frayne, "Celtic Symbology and Motifs," Celtic

Motifs web site, <http://www.thingzoz.com/celtic/index.htm>.

10. The Fajada Butte "Sun Dagger" petroglyph is an extremely

sophisticated astronomical tool, indicating summer and winter solstices,

vernal and autumnal equinoxes, and lunar standstills. It consists

of one large counterclockwise spiral and one smaller clockwise spiral.

Three upright sandstone slabs direct the sunlight so that just before

noon on the summer solstice a downward pointing, vertical "dagger"

bisects the center of the large spiral. On the winter solstice two

vertical daggers of sunlight rest tangentially to this spiral. On

both equinoxes a downward pointing triangle of light bisects the

small spiral, which is located above the center and to the left

of the large spiral. See Anna Sofaer's excellent web site The

Solstice Project.

11. "Techqua Ikachi: Land and Life, the Traditional View,"

44 Newsletters of the Hopi Nation, online publication. <http://www.jnanadana.org/hopi/techqua_ikachi_i.html>

12. Carlos Castaneda, Tales of Power (New York: Pocket Books/Simon

& Schuster, 1976, 1974), p. 116 ff.

13. Page Bryant, Terravision: A Traveler's Guide to the Living

Planet Earth (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991), pp. 38-39,

p. 89 and p. 91.

14. Richard Leviton and Robert Coons, "Ley Lines and the Meaning

of Adam," Anti-Gravity & The World Grid, David Hatcher

Childress, editor (Kempton, Illinois: Adventures Unlimited Press,

1997, 1987), p. 146.

15. Ibid., p. 150.

16. Ibid., pp. 185-186.

17. Graham Hancock, The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the

Lost Arc of the Covenant (New York: Touchstone Books/Simon &

Schuster, 1993, 1992), p. 6.

18. William Blake, David V. Erdman, editor, The Poetry and Prose

of William Blake (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1970,

1965), p. 25.

19. Waters and Fredericks, Book of the Hopi, pp. 138-141.

20. In Lakota (Sioux) this phrase is Chante Ishta, "...with

which we see and know all that is true and good." Joseph Epes

Brown, The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven Rites

of the Oglala Sioux (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1979,

1971, 1953), p. 42.

21. A.M. Stephen quoted in Patterson, Hopi Pottery Symbols,

p. 34.

22. New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology (London: The Hamlyn

Publishing Group Limited, 1972, 1959), p. 60.

23. Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), The Serpent Power: the

Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga (New York: Dover Publications,

Inc. 1974, 1919), pp. 1-3.

24. Dennis Tedlock, translator and commentator, Popol Vuh: The

Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life (New York: Touchstone Books,

Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1986, 1985), p. 341.

25. Garrick Mallery, Picture Writing of the American Indians,

Vol. 2 (New York, Dover Publications, Inc. 1972, 1893), pp. 701-702.

26. Waters and Fredericks, Book of the Hopi, pp. 9-11.

27. Joseph Campbell, The Inner Reaches of Outer Space: Metaphor

as Myth and as Religion (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers,

1988, 1986), p. 82.

28. Ibid., p. 83 and p. 88.

29. Ibid., pp. 90-91.

30. Ibid. pp. 89-90.

31. J.E. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols (New York: Philosophical

Library, 1971, 1962), p. 306.

32. Siddhartha Gautama the Buddha, "The Fire Sermon,"

The Teachings of the Compassionate Buddha, E.A. Burtt, editor

(New York: New American Library/Mentor Books, 1955), p. 97.

33. Revelation 1:8.

34. Erling Duus, The Tragic, Sacred Ground (Freeman, South

Dakota: Pine Hill Press, 1989), p. 67.

35. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, p. 305.

36. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man (New

York: Harper Colophon Books/Harper & Row, Publishers, 1975,

1959), p. 148.

37. Mircea Eliade, Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries

of Birth and Rebirth (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers,

1975, 1958), p. 14.

38. "Techqua Ikachi," op. cit.

39. Edward S. Curtis, Frederick Webb Hodge, editor, The North

American Indian: Hopi, Vol. 12 (Norwood, Mass.: The Plimpton

Press, 1922), p. 103.

40. Hamilton A. Tyler, Pueblo Gods and Myths (Norman, Oklahoma:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1984, 1964), pp. 214-1-6.

41. Katherine Cheshire, Hopi Elder, Touch

The Earth Foundation, online publication, <http://www.wolflodge.org/wolflodge/spiritsakes/spirits.htm>.

42.

Chief Dan Evehema, "Message

to Mankind," online publication, <http://www.thehopiway.com>,

see Messages link on the left.

43. William Butler Yeats, M.L. Rosenthal, editor, The Selected

Poems of William Butler Yeats (New York: Collier Books, 1968,

1962, 1934, 1931), p. 91.

![]()