from

Chapter 5: A Window Onto the Cosmos

(Please

be patient while graphics are loading.)

Carving the Cosmos: A Petroglyphic Solstice Marker and

Earth/Star Map

At Homol’ovi, Arizona

by Gary A. David

Copyright

© 2000 by Gary A. David.

|

Across

ocher and salmon colored sandstone a shadow crawls like a shallow pool of water

flowing in slow motion. Its fuzzy penumbra gradually slides over the spiral

petroglyph pecked into smooth rock. We know this movement is the result of the

greater spinning of our planet in relation to a stationary sun. However, for

the Hisatsinom (a.k.a. the Anasazi) shadows were animate beings whose movements

reflected those of the Underworld spirits. “The shadow, the voice, the face,

and even the will of the dead may cling to the living. They thus may be thought

to exist in a spirit world.”

1

The

Pueblo people conceived of the spirit world as being coterminous with the chthonic

zone of the previous Third World, accessed primarily through the Sipapu

at the bottom of the Grand Canyon just east of the confluence of the Colorado

and the Little Colorado Rivers. Thus, the duality of light and dark, day and

night, summer and winter, etc. inherent in the Hisatsinom cosmology was infused

with an animism that allowed the great sun god Tawa

to interact with the lesser dusky revenants who periodically return from the

subterranean realms via the various manifestations of the Sipapu. For

us the importance of such a natural phenomenon is mostly esthetic, exemplified

by lavish Sierra Club photography depicting shadows which play across sensuously

curving sandstone sunlit in stark, vibrant colors. For the Ancient Ones, however,

shadows were

supernatural

'shades'

imbued with a mysterious vitalism that imparted not only beauty in the eye of

beholder but awe as well. “The play of sunlight and shadow along a wall in a

room or across a landscape may deeply interest or even visually thrill us, but

for a people who live by the sun and depend heavily on it for knowing the seasons,

the day, or the time, the interaction of light and shadow takes on a much deeper

meaning. For them, displays of light and shadow may extend into the realm of

the sacred; they constitute a sacred appearance, or hierophany (from the Greek

words hieros, ‘sacred’ and phaino, ‘to reveal or make appear.’”

2

Four major ruin sites and a few outlying sites exist in

the vicinity of Homol’ovi

Ruins State Park near Winslow, Arizona. On the east side of the Colorado

River we find Homol’ovi I and II; on the west side of the river are Homol’ovi

III and IV, all settled at slightly different periods. Homol’ovi

IV, a 150 room masonry pueblo built in a stepwise manner on the east and

south sides of a small butte as well as on its top, was the settled in A.D.1260

by immigrants from the Hopi Mesa region. It was occupied only for a period of

twenty years, which might have been the result of an influx of clans moving

from the south to build some of the other sites at Homol’ovi.

3

A half mile south and nearer to the Colorado River, Homol’ovi

III was a 50-room pueblo with three rectangular kivas and one masonry great

kiva built in A.D. 1280 at about the time of the abandonment of Homol’ovi IV.

Because of the style of ceramics found --black-and-white painted on red ware--

plus the larger room construction of masonry and puddled adobe 4,

archaeologists hypothesize that the builders of this pueblo were Mogollons who

migrated from the Silver Creek region of eastern Arizona near the contemporary

towns of Snowflake and Showlow. As with Homol’ovi IV, this pueblo’s life span

was brief; it was abandoned in the early 1300s due to the extensive flooding

which followed the Great Drought of 1276-1299, the earlier event perhaps partially

causing the migration to Homol’ovi III in the first place.

On the eastern side of the Little Colorado River the comparatively

large, 900 room pueblo of Homol’ovi

I was begun in 1280 at about the same time as Homol’ovi III and perhaps

assimilated some of the people from the abandoned Homol’ovi IV. Some portions

of Homol’ovi I were two stories high, and it also contained a number of open

plazas and kivas.

One of the latter measuring fourteen feet wide and twenty feet long was paved

with flagstones and had a stone bench on the south end and a number of loom

holes on the east and west sides. This highly stratified pueblo which used a

variety of masonry and adobe construction styles suggests much renovation during

its relatively long history. It was abandoned in circa A.D. 1390 after a period

of massive flooding.

About three-and-a-half miles north on a low knoll rests Homol’ovi II, the largest

ruin in the area with over 1200 rooms, 40 kivas, three large plazas, and a ramada

three-hundred feet long on the south side. Beginning construction in A.D. 1330,

it gradually became the focal point of the trade network in the region. This

pueblo was also the center of the katsina

cult that developed in the late thirteenth century. In addition to numerous

representations of these spirit beings on ceramic bowls and petroglyphs, two

beautifully painted murals were found on the walls of two separate kivas at

Homol’ovi II: one depicts the San Francisco Peaks where the katsinam

live, while the other shows two katsina dancers with cotton kilts. Homol’ovi

II was abandoned at about the same time as Homol’ovi I near the end of the fourteenth

century.

We can imagine members of the first village settled at Homol’ovi gathering before

dawn on the summer solstice in an alcove-like enclosure of rock not far from

their pueblo. Here they await the sacred interplay of shadow

and sunlight. The main panel,

which faces eastward, is created by a vertical sandstone fault about twenty-five

feet long and fifteen feet high. It is capped by an overhanging slab that extends

horizontally about four feet to

the east. Approximately ten feet to the east is

a round-topped boulder that forms the inner east wall of the enclosure and casts

a curved shadow upon the main panel. Open to the south but blocked to the north

by broken chunks of rock heaped higher than their heads, this enclosure protects

the observers who sit cross-legged and close together on the ground, gazing

in rapt attention at the primary grouping of petroglyphs on the main panel.

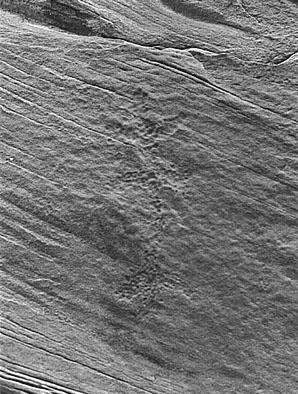

On

the left (south) side of this panel near the bottom are clan markings. These

include a bear print, a human left hand print, possibly a badger claw (all arranged

horizontally), and a snake glyph looping horizontally above these (photo upper

left).

Just

to the right of this grouping is a long migration line that curves upward and

to the right, ending in a spiral comprised of four revolutions. Near

the bottom of the panel immediately to the right of this "trail"

is a somewhat circular "corral" that contains a zoomorph in profile.

Its head faces obliquely upward and to the right. In between the trail and the

left side of the corral is a vertical zigzag snake, while on the left side is

a pair of similar zigzag

snakes,

all of which have recently

been

defaced. Slightly above and

a few inches to the right of

the

spiral is a glyph depicting some sort of V-shaped "artifact" pointed

downward. To the right of this we find a large equilateral cross formed by an

oblique axis we shall call the "plumed serpent," carved from the top

left to the lower right of the panel. A "vertical axis" bisects this

oblique line and extends downward to nearly the same height as the bottom of

the corral, ending in a cupule about one inch in diameter. To the far right

(or north) at the same height as the center of the cross, there is a petroglyph

of an antelope-- a pronghorn in profile with its head facing to the left. Viewed

as a composite, these petroglyphs are about eight feet long.

The sun priest's low,

plaintive chant mingles with pungent smoke of juniper

leaves smoldering on a chill desert wind. About

5:15 a.m. the upper arc of the sun’s disk flows

like molten gold over the edge of the world. Within a few moments orange sunlight

bathes the top of the main panel, while the eastern wall of the enclosure begins

to cast a gently arcing, horizontal shadow. Soon this shadow-being starts to

crawl down the panel, passing consecutively

through a number of petroglyphs: the head of the

plumed serpent, the center of the spiral, the V-shaped artifact, the intersection

of the cross, the antelope, the corral, and the clan petroglyphs on the far

left. One section on this generally horizontal shadow has two right angle jogs

that first nestle the plumed serpent’s head as they pass through and then follow

the slight curve on the upper portion of the vertical axis.

This progression has already taken over an hour when the shadow finally touches

both the cupule at the bottom of the cross’s vertical axis and the beginning

of the trail at the lower left. The horizontal shadow continues downward for

another half hour, after which it finally leaves the panel altogether. Chants

to both the sun god Tawa and the chthonic spirits accompany this “sacred appearance,”

as an aura of the miraculous pervades the gradually warming air of morning.

Just

as this shadow creature is departing, another one formed by the overhanging

slab begins to proceed down a yet unmentioned pair of vertical rows of dots

which are located at the very top right of the panel. Each row contains either

twenty or twenty-one pecked dots, but erosion now makes it impossible to determine

the exact number. Because of the irregularities on the edge of the horizontal

slab overhead, its adumbration has a number of bumps and notches that interact

with

specific petroglyphs during

various stages of the spectacle. (See Diagram 1 below.) In comparison with the

former shadow discussed, this one will create a dynamic synergy of sunlight

and shade that staggers the mind. Not unlike a written account of the movements

in a ballet or --more germane to our discussion-- the ritual acts of a katsina

dance, any description of this presentation is bound to fall short of its actual

intricacy and sanctity. In other words, the play’s the thing.

For about an hour and forty-five minutes the “large bulge” on the right side

of the shadow has been inching down the two vertical parallel

rows

of dots. At 8:45 a.m. as it reaches the bottom of these rows, the “small bulge”

is poised directly above the antelope, the “nipple” rests above the vertical

axis, and the “large notch” hovers above the head of the plumed serpent.

Nearly an hour later

the horizontal section of the shadow to the right of the large notch bisects

the antelope, while the

horizontal section to the left bisects the V-shaped artifact. At

this point the notch itself is lodged on top of the vertical axis.

After

five minutes this same horizontal section to the right reaches the feet of the

antelope, while the horizontal section to the left touches the lower tip of

the artifact. Simultaneously, the lower left side of the notch is almost at

the center of the cross. In addition, a smaller notch which has formed to the

left of the larger one is lodged between the artifact and the spiral. Furthermore,

the curving shadow to the left of this smaller notch grazes the upper part of

the spiral.

In

seven minutes the left side of the shadow reaches the center of the spiral,

and the large notch begins traveling down the lower part of the oblique plumed

serpent.

Approximately

twenty minutes later the large notch reaches the end of the plumed serpent,

while the left side of the shadow touches the outer left curve of the spiral,

where it will remain for nearly two more hours.

As the small notch begins traveling down the bottom part of the vertical axis,

the left side of the large notch touches a small cupule located at the tail

of the plumed serpent. (it is now 10:40 a.m. As the reader may have noticed,

the sun’s ascension causes the shadow to move generally from the upper left

to the lower right of the panel.)

After

about another half hour, the horizontal lower edge of the whole shadow has moved

off the panel, though its left side still rests on the left side of the spiral.

Around noon the shadow which has obscured the spiral since around 10:00 a.m.

begins to move again, back though its rings toward the right.

Thus far, we have been dealing primarily with shadow against stone. Now another

element enters into the play. Near the top left side of the whole shadow, a

triangle of light forms. A few minutes after noon this triangle begins to move

downward toward the spiral. At about 12:30 p.m. this triangle splits into two

smaller triangles of light. When these lights pass directly into the center

of the spiral, however, they merge.

This

one triangle proceeds downward and passes out of the spiral, where it again

splits into two smaller triangles of light. The left side of the whole shadow

is now

passing

through the corral, the only time it is obscured.

Thus

far we have been witnessing an unequivocal hierophany. For approximately seven

and a half hours we have seen the worlds of shadow and sunlight interact with

amazing complexity, evoking beyond a doubt the discernible presence of the divine.

But while the bottom of the shadow touches the bottom of the corral, and with

most of the main panel no longer illuminated, something startling occurs. Just

when we think that the sacred show is over, the light leaves the main panel

and leaps across to the smaller panel opposite it, i.e., the inner east wall

of the rock enclosure. A crescent of light with down-turned cusps hovers over

a petroglyph representing an artifact comprised of four crescents arranged on

a vertical shaft. At its top is a small circle, and just beneath that is a crescent

with upturned cusps that mirrors the crescent of sunlight with breathtaking

congruence.

|

|

|

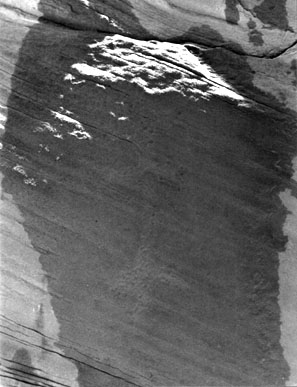

On

a smaller panel opposite main panel, a vertical artifact with perpendicular

crescents.

|

After

sunlight leaves the main panel, it hovers over top crescent of artifact.

(Petroglyph dampened to accentuate features.)

|

This

artifact is located directly across from the V-shaped artifact on the main

panel. To the right of the former artifact is a zoomorph which is also directly

across from the one inside the corral on the main panel. To the right and

a few feet below this animal on the smaller panel is a “double rainbow” with

a dot in the middle, which is across from the clan markings on the main panel.

At about 1:00 p.m. when the sunlight has left the main panel altogether, a

serrated shaft of light on the smaller panel advances from the lower left

toward the double rainbow on the lower right. It ultimately reaches the dot

at the center, as the whole panel is bathed in the luminous power of Tawa.

Between the droning chants of the sun priest and his offerings of corn meal

and paho feathers, he has been explaining to the people of the village the

subtle ritual performed jointly by the sun god and the Underworld spirit shadows.

Now on this longest day of the year when Tawa again begins his southward journey

along the sunrise and sunset horizons, the balance of the world is once more

restored.

What

is the significance of all this iconography vis-à-vis the interplay of dark

and light? Let us discuss the discrete elements of this configuration of rock

art, looking at the cultural symbology of each separate petroglyph.

When first viewing this group of petroglyphs, the eye

is immediately and instinctively drawn toward the spiral, which is the latter’s

primary function. This inward swirling form creates the illusion of three

dimensional space into which the perceiver’s eye is pulled, whirling toward

the mysterious and transcendental realms of the spiral’s eye. Some believe

that the spiral represents the shaman’s tunnel or portal though which spirit

journeys are made. “The most frequent use of the spiral was to illustrate

emergence or vortex travel from one level of existence to another.” 5

In

the context of Pueblo culture this would signify the passage via the sipapu

between the Third and the Fourth World. It is easy to imagine why the spiral

would also be associated with whirlpools in water and whirlwinds in air. Polly

Schaafsma, an expert in the field of rock art, has given a number of interpretations

for this ubiquitous petroglyph of the Southwest: “...it may symbolize water

or wind, or have an association with the sun, especially if the rock art is

positioned so that it interacts with a beam or shaft of light. To modern Hopis

and Zunis the spiral represents migrations.” 6

This latter comment is especially true if the end of the spiral is extended

into a “trail,” which is precisely the case of the spiral at Homol’ovi we

have discussed. This is connected to a very long, curving path that terminates

at a number of clan petroglyphs, in particular the Bear, the Snake, and perhaps

the Badger. The loops of the spiral are also thought to represent the number

of rounds or pásos made in ancient migrations to each of the four directions.

7 One interpretation

closely associates this petroglyph with a primary Hopi deity: “...counter

clockwise spirals are reported to symbolize the ‘path of Masau (Maasaw) bringing

rain’ and ‘members of Chief kiva form (a) spiral at Winter Solstice’...” 8

(As the Hopi god of the earth, death, and the Underworld, Masau’u

plays a significant role in the December solstice ceremony known as Soyal.)

One source geographically particularizes the symbology of the spiral by relating

it directly to the Sipapu in Grand Canyon and the Hopi salt gathering

ceremony performed there. “Close to this deposit [of salt] the river forms

a series of eddies which is supposed to mark one of the entrances to the house

of Masau, and in these eddies the Hopitus, when they go there

to gather salt, toss their breath feathers and [corn] meal offerings to Masau.”

9 Thus, in this context the spiral/whirlpool

is known as “the gate of Masau’s house.” This is an important element

in constructing the stone “map,” the solstitial aspects of which are described

earlier in Chapter 5 (not shown).

Another element crucial in our conceptualization of

this Homol’ovi petroglyph grouping as a cartographic representation is the

large equilateral cross to the right of the spiral. Of course, small equilateral

crosses represent stars, but this larger one could be construed as a modified

swastika, a common symbol in Anasazi, Sinagua and Mogollon iconography for

the land, especially the center of the land. 10

“We

can now see that the complete pattern formed by the migrations was a great

cross whose center, Túwanasavi [Center of the Universe], lay in what is now

the Hopi country in the southwestern part of the United States, and whose

arms extended to the four directional pásos.” 11

One intriguing variation of the Homol’ovi cross can be found in its oblique

axis, which we have labeled the “plumed serpent.” In the Pueblo frame of reference,

snake iconography represents rivers in particular and water in general-- perhaps

in part because the reptilian resembles the riparian morphologically. “The

snake’s undulations also suggest the pattern of lightning, and the snake strikes

swiftly, as lightning strikes.” 12 If

the Anasazi/Hisatsinom were lucky (or more correctly, punctilious in regard

to their ceremonial cycle), lightning was accompanied by copious amounts of

rain. As the northern equivalent of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl or the Mayan

god Kukulkan, the plumed (or horned) serpent, called Palulukang by the Hopi,

acts as a guardian of underground springs. 13

Furthermore, it serves as a universal provider, offering its bounty in a land

of scarcity. “It is a great crested serpent with mammae, which are the source

of the blood of all the animals and of all the waters of the land.” 14

This hybrid creature unites the three planes of subterranean, terrestrial,

and celestial by its corresponding characteristics of reptile, mammal, and

bird. Especially in the desert the serpent symbolizes liquid life itself,

either as an indispensable potable substance (i.e., the primordial milk of

existence) or as a vital fluid flowing through the veins of all beasts.

If we orient the elements of the Homol’ovi petroglyph

to various geographical and human-made features of the landscape, a precise

map of the southwestern edge of the Colorado Plateau begins to take shape.

The center of the equilateral cross, of course, corresponds to Tuuwanasavi,

the "Center of the World," or the Hopi Mesas.

At the upper end of the vertical axis is a natural hole in the rock over which

a somewhat eroded but recognizable small equilateral cross has been abraded.

This correlates to the ruins of Betatakin and Kiet Siel in Tsegi

Canyon within the borders of Navaho

National Monument due north of the Hopi Mesas.

Approximately the same number of inches below the intersection point, just

to the right of the vertical axis, is a faint

mark in the rock that represents Homol’ovi itself. If the Hopi Mesas were

indeed first settled circa A.D. 1100, then the Hisatsinom living at this spot

where the petroglyph is located would have certainly recognized the well-established

Center-place off to the north, since this first settlement at Homol’ovi is

dated A.D. 1260. Incidentally, Betatakin and Homol’ovi are equidistant on

this north-south axis and were built at about the same time.

As we have shown, the oblique axis of the petroglyph

forming a plumed serpent represents water, specifically the Little Colorado

River that snakes from the southeast to the northwest and joins the Colorado

River at the Grand Canyon. To the right on the lower portion of the oblique

axis is an incised mark in the rock just above the extended length of the

serpent. This represents the Canyon de Chelly

pueblos, the construction of which began in A.D. 1060 between the supernova

explosion (1054) and the eruption of Sunset

Crater (1064). The

tip of the serpent’s tail might correspond to the ruins at Casa

Malpais and Raven

Site in

the southeast near the source of the Little Colorado.

To the left on

the upper portion of the oblique axismidway

between the intersection and the serpent’s head is a right angle turn that

represents the Wupatki pueblos, built

in the first few decades of the twelfth century just after the Hopi Mesas

were initially settled. Moreover, the serpent's head could be linked with

the smaller ruins of Glen Canyon along the Colorado River north of the Grand

Canyon. As an extension of the spiral, the “trail” roughly follows the geographic

arcing of the Colorado River as it flows downstream, terminating at a number

of clan petroglyphs, in particular the Bear Clan and the Snake Clan. As acknowledged

in Hopi oral tradition, the migration from the Third to the Fourth World entailed

the use of bamboo boats to escape a tremendous flood. Some believe that the

Hisatsinom traveled upstream and through the Grand Canyon to arrive at the

Sipapuni, at which place they emerged to seek their final destination

upon the Colorado Plateau.

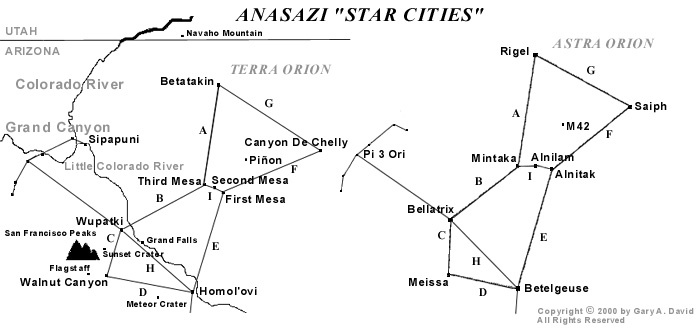

Consistent with the Hermetic theme of “As Above, so Below,” the configuration

of pueblo villages is an analogue to the celestial plane, and the stone map

at Homol’ovi seems to bear this out. To the northeast Canyon de Chelly was

settled first in A.D. 1060, and its correlative star Saiph in the constellation

Orion

has a magnitude of 2.2. 15 (Although

Burnham has 2.06 for Saiph, considerable variation occurs, depending on the

source.) The three Hopi Mesas were next settled, with Shungopovi

on second Mesa established circa A.D. 1100 and Oraibi

on Third Mesa shortly thereafter (Some versions, however, state that the villages

were constructed in reverse order.) Shungopovi’s corresponding star is Alnilam

with a magnitude of 1.7, while Oraibi’s is Mintaka with a magnitude of 2.2.

Walpi

supposedly was settled in the late 1200s, but the village of Koechaptevela

at the base of First Mesa preceded the existence of the former village, so

its date of origin may have coincided with those of Shungopovi and Oraibi.

At any rate, the correlative star of First Mesa is Alnitak with a magnitude

of 1.79, approximately that of Alnilam. To the southwest Wupatki was established

about A.D. 1120, and its sidereal twin is Bellatrix, which has a magnitude

of 1.64. Thus, we can perceive the northeast-southwest axis as part of the

oblique line of the petroglyph. To the south of the Hopi Mesas Homol'ovi IV

was established in A.D. 1260, and its sidereal companion is Betelgeuse, whose

magnitude is 0.7. (However, because it is a variable star it sometimes appears

as bright as Rigel.) To the north is Betatakin, built in A.D. 1260 as well.

Its correlative is Rigel with a magnitude of 0.34. Now we can also perceive

the north-south axis as part of the vertical line of the petroglyph. The reader

may have noticed a proportional relationship between the age of the pueblo

villages and the magnitude of each village’s corresponding star. Specifically,

we find that the relative age of a given ruin or extant village is for the

most part in inverse proportion to the magnitude of its sidereal correlative.

In other words, the older the village the dimmer the star. (We must remember

that a lower magnitude number signifies a greater sidereal brilliance.) To

recapitulate, the oldest villages like those in Canyon de Chelly have the

dimmest stars (i.e., Saiph), while the youngest villages like those at Homol’ovi

and Tsegi Canyon have the brightest stars (i.e., Betelgeuse and Rigel respectively).

Again we must decide whether or not this coincidence is “meaningful.” Perhaps

it is indeed another part of the elegant pattern in which the terrestrial

mirrors the celestial.

|

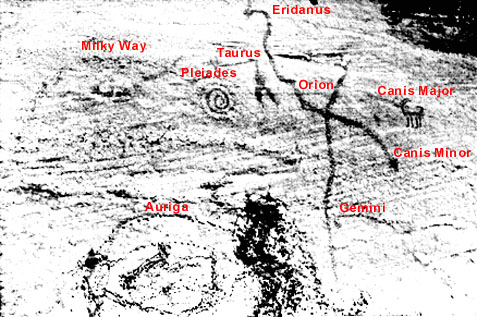

Diagram

1

We

have seen how the large equilateral cross of the Homol’ovi petroglyph represents

both the Hopi Mesa villages at the Center-place and the ruins sites at Tsegi

Canyon, Wupatki, Homol’ovi, and Canyon de Chelly. This Anasazi swastika symbolizing

the land also mirrors the sky, specifically the constellation Orion. The oblique

line forming a plumed serpent corresponds to the Little Colorado River, which

flows into the Grand Canyon. We have also established that the spiral glyph

signifies the gate through which Masau’u descends to his house located just

north of the two great rivers’ convergence. This is the grand Sipapu,

whence the people emerged onto the Fourth World where they now live. On a personal

level this is also the passage way through which the spirit will descend on

its afterlife journey. Equidistant between the plumed serpent and the spiral

is an image we have not yet discussed. A V-shaped artifact points downward,

enigmatically radiating its numinous power. If we look at a sky chart in the

region of Orion, we notice that the V-shaped Hyades of the constellation Taurus

lies adjacent to Orion in the same relative positioning that we find on the

petroglyph. The relationship between Taurus, in particular the fiery red star

Aldebaran, and Sotuknang, the Heart of the Sky God, is an enduring theme in

Hopi mythology. Hence, on this one petroglyph panel at Homol’ovi we unequivocally

find elements that iconographically link both the celestial and the terrestrial.

“On a balance between these two forces, the forces of the sky (or the Above)

represented by Sho’tukünuñwa [Sotuknang], and those of the Below represented

by Pa’lülükoñ [Palulukang], the Hopi universe rests. Symbolically, the two elements

are brought into contact in the making of medicine water [during the Snake Ceremony

in August], where the ray of sunlight flashed into the bowl signifies the Above,

and the water itself, the Below.” 16 In

addition to the petroglyphic constellations of Orion and Taurus, to the left

of the V-shaped glyph is located the spiral, which perfectly corresponds on

the sky chart to the Pleiades, known to the Hopi as either Tsöötsöqam

or Sootuvìipi. 17 Thus we have

here three glyphs in a row which directly correspond to the configuration of

three major constellations.

However, the correlative factors do not stop here. To

the right of the large equilateral cross of Orion is the glyph of the antelope.

Looking to the sky chart in the same relative position, we find the brightest

star in the heavens, Sirius in Canis Major. “‘Now,’ the chief continues, ‘another

star appears in the southeast, Ponóchona [The One That Sucks From the Belly].

This is the star that controls the life of all beings in the animal kingdom.

Its appearance completes the harmonious pattern of the Creator, who ordained

that man should live in harmony with all the animals on this world.’” 18

We should note here that in Hopi cosmology the intercardinal direction of southeast

is totemically represented by the antelope. 19

East of First Mesa nearly 140 miles are the ruins of a grand ceremonial city

in Chaco Canyon, which is represented

in a proportional distance on the Homol’ovi petroglyph by this appropriate zoomorph.

Still other constellations may possibly be portrayed on

this petroglyphic star map. On an extension of the vertical line just below

a gentle curve are two abraded marks on either side of the line. The line continues

downward until it terminates in an abraded mark made inside a natural cupule.

A few inches to the right of this is another slightly larger natural cupule.

Looking at the sky chart, we find this corresponds to the rectangular constellation

Gemini. The upper pair of marks represents Alhena and Mu Gemini, while the lower

pair Pollux and Castor, known to the Hopi as Naanatupkom, or “the Brothers.”

20 Perhaps it is merely a coincidence,

but a natural groove in the panel cuts horizontally just below Betelgeuse and

above Alhena. Terrestrially this could correspond to the Mogollon Rim cutting

across the middle of Arizona, while celestially this might signify the Milky

Way, which the Hopi call Soomalatsi. 21

In addition, the tip of the plumed serpent’s tail which we said plausibly represents

the region the Hopi deem Weenima 22

(the ruins at Casa Malpais and Raven Site) may very well correspond to the constellation

Canis Minor with its bright star Procyon, known to the Hopi as Taláwsohu,

or “Star Before the Light.” 23

Again consulting the sky chart, we find one more constellation

represented on the Homol’ovi petroglyph. The aforementioned corral at first

glance appears somewhat circular, but on closer examination we find that it

looks five-sided. The Anasazi/Hisatsinom clearly had no technical difficulty

incising a perfect circle in stone, if that is what they intended. The deliberately

pentagonal figure, then, very likely corresponds to Auriga. More recently the

zoomorph inside the corral has been badly defaced, so it is difficult to determine

its species, but quite possibly it could represent a mountain goat or mountain

sheep. Having the exact magnitude of Rigel, the brightest astral point of this

constellation is Capella, which means “little she-goat.” 24

The zoomorph inside the corral could indeed be a mountain goat or a mountain

sheep, the latter of which is the Hopi totemic symbol for the southwest-- the

direction where the terrestrial Auriga would be located in our constellatory

schema.

Incidentally, we have already discussed the vertical zigzag

snakes on either side of the corral, which are stylistically different than

the undulating horizontal snake off to the left near the clan glyphs. The zigzag

snakes appear to be more recently incised because the re-patinization is not

as pronounced as it is on the rest of the petroglyph. In addition, these too

have been badly defaced. Initially one is enraged at such wanton destruction

of rock art, but since these zigzag elements do not seem to fit either the conceptual

configuration as we have described it or the style of the rest of the petroglyph

panel, perhaps this was an intentional defacement. Possibly some modern Hopi

tried to erase the negative spiritual effect of such spurious graffiti made

in more recent times, probably by a non-Indian. As with most rock art, a mysterious

conundrum supersedes any such speculations.

To sum up the elements of this earth/star map and solstice marker petroglyph

in terms of the supernal dimension, we have found on the panel all the constellations

of the Winter Hexagon: Orion, Taurus, the Pleiades, Auriga, Gemini, Canis Minor

and Canis Major. In terms of the tellurian dimension, represented by the large

equilateral cross are the villages of the Hopi Mesas as well as the ruins located

at Navaho National Monument, Wupatki National Monument, Homol’ovi Ruins State

Park, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument. What we have called the plumed

serpent represents the Little Colorado River and the on the left side of the

panel the V-shaped artifact corresponds to all the smaller ruins in the Grand

Canyon. On the right side of the panel the antelope signifies the magnificent

Anasazi/Hisatsinom ruins in Chaco Canyon. The spiral corresponds to the Hisatsinom’s

Place of Emergence in the Grand Canyon, while its extension represents the Colorado

River flowing southward.

|

|

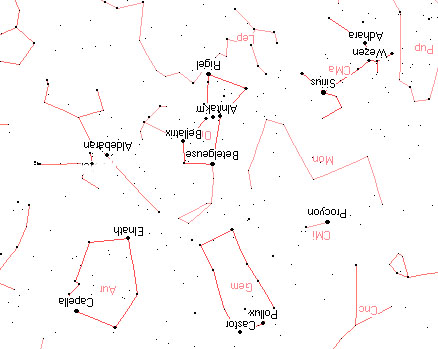

Constellations

on the main petroglyph panel proportional to the sky chart.

|

|

|

Sky

chart rotated 180° to correlate with petroglyph orientation.

|

"Amlodhi was identified, in the crude and vivid imagery of the Norse, by the ownership of a fabled mill which, in his own time, ground out peace and plenty. Later, in decaying times, it ground out salt, and now finally, having landed at the bottom of the sea, it is grinding rock and sand, creating a vast whirlpool, the Maelstrom (i.e., the grinding stream, from the verb mala, “to grind), which is supposed to be a way to the land of the dead. This imagery stands, as the evidence develops, for an astronomical process, the secular shifting of the sun through the signs of the zodiac which determines world-ages, each numbering thousands of years. Each age brings a World Era, a Twilight of the Gods. Great structures collapse; pillars topple which supported the great fabric; floods and cataclyms herald the shaping of the new world." 25

In the context of our star map petroglyph, this all seems vaguely familiar. In lieu of the marine location found in many of the mythic renditions, our desert “mill” located at the bottom of Grand Canyon is represented by the spiral or whirlpool. Also known as the gate of Masau’u, it leads to the land of the dead. The Lord of the Mill in one variation is Saturn/Kronos 26 , who is archetypally related to the Hopi god of the Underworld named Masau’u. The direction of the mill was generally thought to be northwest, “...where... Kronos-Saturn is supposed to sleep in his golden cave notwithstanding the blunt statement (by Homer) that Kronos was hurled down into deepest Tartaros.” 27 At this point we probably don’t need to be reminded that the Sipapu is located northwest of the Hopi Mesas.

In the variegated terms of the mythological logic so assiduously explicated in Hamlet’s Mill, the friction caused by the turning of the quern also produces fire at the axis mundi. 28 Masau’u, earth god of fire, is translated into Orion of the (eastern) Horizon, which, resembles the firedrill or fire sticks sparking the sun god Tawa into his daily existence during the end of the annual ceremonial cycle in July. Although the Hopi Tuuwanasavi is not directly coextensive with the whirlpool of the Grand Canyon, it is contiguous, and, given the wide range of Anasazi/Hisatsinom migrations, close enough to be conceptualized as part of the Center-place.

The

recurrent image of salt in the so-called mythological “implex” described by

Santillana and Dechend corresponds to the destination of the salt collecting

expeditions made by the Hopi and presumably by their ancestors as well. In fact,

the Hopi term for the Grand Canyon is Oentupqa, or Salt Canyon. This theme is

related to the image of the “Saltwater-Tree” of the Cuna Indians who live in

Panama as well as on the San Blas Islands, and whose ancestors conceivably had

trade relations with the Anasazi/Hisatsinom “God’s whirlpool” is located beneath

this tree, which, when chopped down by Tapir (a sun god somewhat resembling

Quetzalcoatl), unleashes a great flood to form the world’s oceans. 29

As recalled in Hopi mythology, a mighty deluge caused the destruction of the

Hopi Third World.

According to the co-authors, the devastation of the World Tree or world pillar celestially correlates to the gradual shifting --one degree every seventy-two years-- of the vernal equinox sunrise point from one zodiacal constellation to the preceding one (hence the precession of the equinoxes), occurring once every 2,160 years and completing the full cycle once every 25,920 years. Instead of an actual tree, which is not a very potent image in the cosmology of desert dwellers, a hollow bamboo reed through which the virtuous people emerged from the lower Third to the upper Fourth World finally comes crashing down (or is cut down), leaving the wicked either imprisoned inside it or stranded below in the nether realm.

The

Norse version of the tale has an additional element found on our star petroglyph.

Corresponding to the whirlpool spiral, Hvergelmir, whose name literally means

“bubbling or roaring cauldron,” is the source and subsequent destination of

all the earth’s waters. It lies beneath the third root of the World Tree, an

ash named Yggdrasil. This root extends into Niflheim, the dark abode of the

Underworld, and is gnawed upon by Nídhögg, a flying dragon who also slowly devours

the bodies of the dead. 30 As we have

stated, the plumed serpent is represented by an oblique line on the petroglyph.

If we conflate Palulukang and Masau’u/Orion, contained therein is the vitalizing

force of water and the mortuary aspect of a subterranean denizen, both of which

we find in the figure of Nídhögg. Incidentally, the harts nibbling on the shoots

of Yggdrasil could plausibly correspond to the zoomorphs on the Homol’ovi petroglyph.

Petroglyph found in the vicinity of the earth/star map.

On far left Masau'u as god of earth is on the same plane as zoomorphs at center and far right. Seen below, a pair of snakes with bifurcated tongues rises from the Underworld. Seen above, a pair of Palulukang figures flies horizontally through the sky, their bodies jointly forming the glyph for water. At the center a horizontal, undulating line from left to right bisects a cleft (natural?) in the rock (possibly representing the Grand Canyon) and ends with a straight line that is crossed by a perpendicular T-shaped figure (perhaps the Hopi Tuuwanasavi, or the Center of the World). Two circles, each with a straight line streaming from it and one with a dot at its center, appear to be either comets or meteors.

Santillana

and Dechend also discuss in sidereal terms the Platonic cosmology found in the

Timaeus. “When the Timaean Demiurge had constructed the ‘frame,’ skambha

[Sanskrit word for axis mundi], ruled by equator and ecliptic--called

by Plato ‘the Same’ and ‘the Different’--which represent an X (spell it Khi,

write it X ) and when he had regulated the orbits of the planets according to

harmonic proportions, he made ‘souls.’” 31

(These souls, by the way, are equal in number to that of the stars, and each

soul is assigned to a given star to which it returns after the death of the

body.) In addition to a swastika’s representation of land, the chiasmic icon

of the star petroglyph might also jointly refer to the celestial equator and

the ecliptic. As heretofore stated, the former currently passes very near Oraibi/Mintaka,

while the latter always passes through Gemini, just above the right hand of

Orion and between the horns of Taurus. The precise location in the night sky

of the latter was once, a very long time ago, also the fiducial point, i.e.,

the place where the equator crosses the ecliptic. At the present this locus

is located between Pisces and Aquarius-- hence we are entering the celebrated

“Age of Aquarius.” However, about 6,500 years ago the fiducial point of the

vernal equinox was located between Gemini and Taurus with the Milky Way passing

directly through it. For the Anasazi/Hisatsinom this date, archaeologically

speaking, places it squarely in the middle of the Archaic period. For the Hopi

this may correspond to the First World, the pristine era of the cosmogony. For

classical writers it was the Golden Age. The 5th century A.D. Latin grammarian

and philosopher Macrobius states that during this age souls ascended through

the “Gate of Capricorn” and descended to be reborn through the “Gate of Cancer.”

32 Because of the precession of the equinoxes

caused by the slight wobble of the Earth’s axis, these respective gates in fact

are located between Scorpius and Sagittarius on one end of the Milky Way and

Taurus and Gemini on the opposite end. In terms of our star petroglyph the forked

icon represents Taurus (recalling the Chinese “Gate of Heaven”), located terrestrially

in the the Grand Canyon, which, as we have stated, is an important pathway for

the katsinam or spirits in their afterlife journey. Thus, in 4500 B.C.

the place where the celestial equator crosses the ecliptic was at the heart

of the galactic plane. This “stargate,” so to speak, functioned as an interdimensional

portal through which souls could pass into this life.

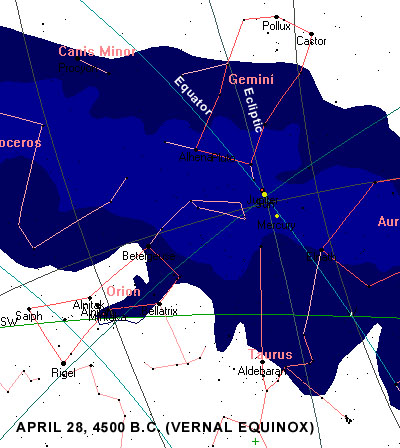

|

|

Stargate,

where the celestial equator crosses the ecliptic at the center of the

galactic plane, or the Milky Way. The green line is the western horizon.

Incidentally, on this date the Sun is conjunct Jupiter, a strongly individualistic

and optimistic aspect.

|

In

discussing our star map petroglyph vis-à-vis contemporary notions of cartography,

we must remember that the former is conceptual rather than proportionally representational.

Archaic societies were not interested in producing scale maps of either the

earth or the sky. For a rendering of mythic symbology in rock art it was sufficient

to contain merely the essential elements, as does the petroglyph at Homol’ovi.

“That there is a whirlpool in the sky is well known; it is most probably the essential one, and it is precisely placed. It is a group of stars so named (zalos) at the foot of Orion, close to Rigel (beta Orionis, Rigel being the Arabic word for ‘foot’), the degree of which was called ‘death,’ according to Hermes Trismegistos, whereas the Maori claim outright that Rigel marked the way to Hades (Castor indicating the primordial homeland). Antiochus the astrologer enumerates the whirl among the stars as Taurus. Franz Boll takes sharp exception to the adequacy of his description, but he concludes that the zalos must, indeed, be Eridanus ‘which flows from the foot of Orion.’” 33

The spiral of our star petroglyph is probably closer to the left shoulder of Orion than the left foot, but the significance of the icon still remains. The Greek word zalos may be related to a combination of the intensive za- and the eleventh letter of the Greek alphabet lambda, which is V-shaped-- thus indicating Taurus and the V-shaped artifact. The great sage Hermes Trismegistus (whose Egyptian name was Thoth) states that the stars near Rigel signify death, and this is borne out in Anasazi/Hisatsinom cosmology by the glyphic depiction of the Grand Canyon, the great Sipapu. The name Eridanus literally means “the river,” and head of the plumed serpent could indeed represent the upper Colorado River. The plume on the snake’s head extended vertically for a few feet could possibly even correspond to the Green River which flows from the north to join the Colorado River in Utah.

In

summing up the aspects main petroglyph panel at Homol’ovi, we find that it functions

as a multifunctional device using natural and man-made elements to produce a

dramatic interplay of light and shadow. Manifesting a stunning complexity and

beauty, this example of rock art carved probably in the late thirteenth century

serves as both a terrestrial cartography associated with the migrations of various

clans and a sky chart establishing the template of Orion and other constellations

upon the earth. In addition, it is an highly accurate solstice marker announcing

the longest day of the year when the sun god Tawa reaches his summer house on

the northeastern horizon. The purpose of the two parallel rows of dots at the

top right of the main panel is at present undetermined, but may yet prove to

have some supernal function, perhaps lunar.

For us securely ensconced in the secular world of rationalism, scientific empiricism,

and technological gadgetry, the solstice marker and earth/star map is a mute

mystery whose deeper implications have been irretrievably lost in the intervening

seven hundred years of cultural and psychological dislocations. Beyond the academic

speculations it engenders, this rock surface provides a dream screen upon which

we project our desires for a unified cosmology complete with its holistic framework

of ritual and myth. For its makers, on the other hand, the petroglyph panel

was undoubtedly a manifestation of the numinous forces inherent in a vibrant

world where the membrane between the physical and the spiritual was as diaphanous

as a breath.

Archaeological evidence shows that the average life expectancy of an Anasazi

(at least in Chaco Canyon) was a mere twenty seven years, and only five to fifteen

percent lived to age fifty. 34 On the

other hand, we contemporaries are allotted our three score and ten, which no

doubt will soon be extended by a welter of wonder drugs, nanotechnology, and

genetic manipulation. Do we not, as a result, have a tendency to look back through

the distorted lens of temporal chauvinism with some measure of pity for the

brief life span of these so-called primitive people? In an age of chaos when

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” 35

and the world appears to be on the brink of an absolute holocaust, are we not

the ones instead who should be pitied? The carved rock at Homol’ovi remains

stoically silent-- the enduring recurring rhythms of sunlight and shadow its

only refrain.

an excerpt from Chapter 5 of The Orion Phenomenon

(a work-in-progress).

Copyright

© 2000 by Gary A. David. All rights reserved

Any

use of text or photographs without the author's prior consent is expressly forbidden.

Contact: e-mail islandhills@cybertrails.com

Footnotes

1.

Hamilton A. Taylor, Pueblo Gods and Myths (Norman, Oklahoma: University

of Oklahoma Press, 1984, 1964), pp. 273-274

2. Ray A. Williamson, Living the Sky: The Cosmos

of the American Indian (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press,

1989, reprint 1984), p. 92

3. William H. Walker, Homol’ovi: A Cultural

Crossroads (Tucson, Arizona: Arizona Archaeological Society, Homol’ovi Chapter,

1996), pp. 15-30

4. It is a common misconception that the Spanish

introduced adobe construction to the New World.

5. James R. Cunkle and Markus A. Jacquemain, Stone

Magic of the Ancients: Petroglyphs, Shamanic Shine Sites, Ancient Rituals (Phoenix:

Golden West Publishers, Inc. 1996, 1995), p.164

6. Polly Schaafsma, “Rock Art at Wupatki-- Pots,

Textile, Glyphs,” Wupatki and Walnut Canyon, edited by David Grant Noble

(Santa Fe, New Mexico: Ancient City Press, 1993, 19870, p. 22

7. Frank Waters and Oswald White Bear Fredericks,

Book of the Hopi (New York: Penguin Books, 1987, reprint 1963), p. 104

8. Nancy Olsen quoted in Sally J. Cole, Katsina

Iconography in Homol’ovi Rock Art, Central Little Colorado River Valley,

Arizona (Phoenix: Arizona Archaeological Society, March 1992), p. 105

9. A.M. Stephen quoted in Alex Patterson, Hopi

Pottery Symbols (Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Books, 1994), p. 28

10. This image is far older than the Nazi regime

and has a sacred rather than an malevolent connotation.

11. Waters and Fredericks, Book of the Hopi,

p. 113

12. Patricia McCreery and Ekkehart Molotki, Tapamveni:

The Rock Art Galleries of Petrified Forest and Beyond (Petrified Forest,

Arizona: Petrified Forest Museum Association, 1994), p. 16

13. Cunkle, Stone Magic of the Ancients,

p. 151

14. Alex Patterson, A Field Guide to Rock Art

Symbols of the Greater Southwest (Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Books, 1992),

p. 158

15. Mark A. Haney, Skyglobe 2.04 for Windows

[floppy disk] (Ann Arbor, Michigan: KlassM Software, 1997)

16. Richard Maitland Bradfield, An Interpretation

of Hopi Culture (Derby, England, published by the author, 1995), p. 275

17. Ekkehart Malotki, editor, Hopi Dictionary:

A Hopi-English Dictionary of the Third Mesa Dialect (Tucson, Arizona: University

of Arizona Press, 1998

18. Waters and Fredericks, Book of the Hopi,

p. 150

19. Stephen C. McCluskey, “Historical Archaeoastronomy:

The Hopi Example,” edited by A.F. Aveni, Archaeoastronomy in the New World

(Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1982) p. ?

20. Malotki, Hopi Dictionary

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Waters and Fredericks, Book of the Hopi,

pp. 149-150

24. Jacqueline Mitton, The Penguin Dictionary

of Astronomy (London Penguin Books Ltd, 1993, 1991), p. 61

25. Giorgio Santillana and Hertha Von Dechend,

Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and

Its Transmission Through Myth (Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.,

1998, 1969), p. 2

26. Ibid., p. 148

27. Ibid., p. 239

28. Ibid., p. 140

29. Ibid., p. 213

30. Sturluson, The Prose Edda: Tales From Norse

Mythology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954), p. 43

31. Santillana & Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill,

p. 306

32. Ibid., p. 242

33. Ibid., p. 210

34. Stephen Plog, Ancient Peoples of the American

Southwest (London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd, 1997), p. 117

35. from Y. B. Yeats' apocalyptic poem "The

Second Coming"

![]()